This article is a translation of the work of Syosin Kai, a Japanese researcher of the history of Japan’s game industry. Translation and publication are being done with written permission from the author. We thank Syosin Kai for his contribution.

Please enjoy this article with the following disclaimers in mind:

- This article was written by a person unaffiliated with the industry, based on industry publications from the period in question

- The said publications include many inconsistencies, so some claims do not have conclusive evidence

- Certain publications this article was based on were in later years identified by industry persons as containing inaccuracies

If you were asked to name the creator of the Famicom (NES), who would come to mind first?

Was it Masayuki Uemura, who was in charge of development? Or perhaps the President of Nintendo Hiroshi Yamauchi, who gave it the green light? Maybe Gumpei Yokoi, the creator of the crucial D-pad? Some might say it was Shigeru Miyamoto, who unleashed the Famicom’s full potential with Super Mario Bros.

On the other hand, if you were to mention the name “Masahiro Shindo,” many people would probably respond with, “Who?” Although he is not very well known, Masahiro Shindo is in fact an important figure who had a very strong influence on the Famicom and Nintendo itself. Let’s prove this by tracing his backstory.

Shindo was born in Japan’s Ehime Prefecture in 1941. In high school, he discovered the joy of chemistry, and went on to enroll in his hometown’s Ehime University. He furthered his education at the University’s newly established Department of Industrial Chemistry, going on to work for Mitsubishi Electric Corporation.

Over the course of his first two years at Mitsubishi, he experienced a number of relocations, secondments, and business operations being axed, and he was eventually transferred to a newly established semiconductor integrated circuit (IC) manufacturing plant. This was the first plant that Mitsubishi had established in the semiconductor business. There, he was promoted to section chief, but his interest started to shift to circuit design, rather than finding ways to increase production capacity.

He requested to be transferred from the production line to circuit design, but this request was turned down, so Shindo decided to change jobs.

Masahiro Shindo started working for Ricoh in 1979, at the age of 38. At that time, Ricoh had decided to build a new semiconductor plant. The market for semiconductors was exploding, and Ricoh’s upper management had high expectations. However, the catch was that Shindo was the only one there with experience in the semiconductor business. Shindo had to start by looking for engineers. He secured about 20 people, educated them, and designed a factory – all at the same time. In 1981, the Ricoh Electronics Technology Development Center was completed in Osaka, and the company was finally able to manufacture semiconductors. The only problem was that they had nothing to manufacture yet.

They didn’t have what was most important – orders. Shindo made an effort to obtain internal orders for Ricoh’s office equipment, but even that didn’t lead to much of a response. There was no reason for Ricoh to place an order with themselves, seeing as they had no track record.

After that, they decided to look for customers externally, but again, no orders came. There was no reason to bother placing an order with Ricoh. Even sales efforts with Ricoh’s affiliated component manufacturers didn’t bear fruit.

Shindo then decided to head overseas to pitch sales. Surely, they would get orders from overseas, if not in Japan? However, Shindo was surprised to learn about the state of semiconductors overseas. He encountered so-called fabless companies. This is a type of company that handles only design and delegates manufacturing to other companies. Shindo came across a fabless called VTI (VLSI Technology, Inc.), a venture company that had just started doing business. Shindo succeeded in obtaining an order to manufacture circuits designed by VTI. This was Ricoh’s first job in the semiconductor business.

Although the workload was still small compared to the factory’s capacity, it was a vital opportunity for the personnel to familiarize themselves with the semiconductor business.

After returning to Japan, Shindo made another new encounter: Nintendo. Among the many companies Shindo made phone calls to was Nintendo, which happened to be looking for a semiconductor plant for the Famicom’s launch. However, at the time, established manufacturers were busy with DRAM production, and none of them could afford to take on the production of a new consumer game console. Nintendo had a relationship with Sharp, but they could not use Sharp’s factory because it was busy producing the Game & Watch at full capacity at the time.

That’s where Ricoh came into the picture. From Nintendo’s point of view, this was a godsend. Ricoh’s factory was equipped with state-of-the-art facilities, but only about 10% of its capacity was being used.

Nintendo’s Masayuki Uemura came to negotiate with Shindo. The demands for the Famicom were as follows:

1. Keyboard-less, since it was to be used by children.

2. A performance level so high that no similar product would appear for more than three years.

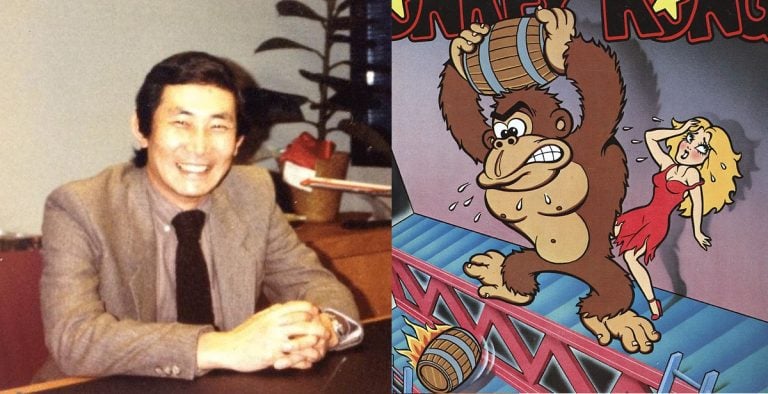

3. Capability to recreate the motion and sound quality of Donkey Kong, which had been a hit on arcade machines.

4. In addition to all of this, it had to be low cost.

It was an unreasonable proposal no matter how you looked at it, but it lit a fire within Shindo. After all, responding to such proposals was exactly what VTI, a fabless company, had been doing. Shindo was excited, for his turn to design circuits had finally come. By a stroke of luck, Ricoh’s semiconductor engineering team had Donkey Kong fans on board, who understood the vision of making Donkey Kong playable on a home console. In addition, there were even staff who had previously worked on the Color TV-Game series released by Nintendo. They and Shindo formulated a plan on how to meet Nintendo’s requirements.

If they wanted to achieve high performance at a low cost, they wouldn’t be able to use general-purpose components. A custom LSI (large-scale integrated circuit) dedicated solely to the Famicom had to be created. Cost is determined by the size and number of chips. Existing arcade game machines used about a hundred general-purpose ICs. Shindo and his team came up with an idea to reduce these as much as possible and make them smaller. The idea that emerged was as follows:

1. Obtain control boards used in arcade game machines and collect the image processing, CPU and memory used.

2. Retrieve chips from collected LSI and take micrographs of them.

3. Cut out and separate the necessary parts and make them into approximately 2-meter squares.

4. Use a 6502 8-bit CPU (which was the world’s smallest at the time), as the heart of the device.

5. Using a copier, reduce the size of the image to 20 cm2.

The concept of extracting only the necessary functions and fitting them into a single chip is the same as the SoC (system-on-chip) concept used in today’s smartphones. Ultimately, not everything could fit on a single chip, so two chips were used, but the development team and Nintendo jointly discussed which functions to utilize and which to reduce.

In the end, Shindo was able to perfectly fulfill Nintendo’s requirements. Ricoh’s semiconductor business soared to new heights following the huge success of the Famicom.

For a time, Shindo became the face of Ricoh’s semiconductor business. However, he later ended up at odds with the company. In 1988, Shindo’s boss resigned. The new boss came in with an arrogant attitude, saying that he was the face of Ricoh’s semiconductor business, having been appointed by the company. An emotional rift started developing between Shindo and the new leadership.

Shindo suggested to the company that Ricoh should take orders for system LSIs and set up a circuit design division. He said that the next generation of semiconductors would be like the kind of design work done by fabless companies like VTI in response to devices like Nintendo’s Famicom.

However, Ricoh refused to accept this proposal. The company believed that the right thing to do was to keep manufacturing existing semiconductors.

The kind of circuit design Shindo envisioned was not possible at Ricoh. Shindo came to this realization and submitted his resignation in 1990. At that time, Shindo’s title was Deputy General Manager of the Electronic Devices Division and Head of the Semiconductor Research Laboratory. His boss accepted his resignation without making any attempts to dissuade him. Thus, Shindo became independent.

After leaving Ricoh, Shindo decided to start his own business. Having witnessed the rise of fabless companies, Shindo founded MegaChips, a semiconductor design subcontracting company, in 1990. It counted seven employees – Shindo himself, five people who followed him from Ricoh, and one new member.

It was then that Shindo became acutely aware of the closed nature of Japanese society. The company could not open a bank account, which was crucial for running a business. Even when he tried to open a personal bank account, which was supposed to be easy, he got flat out rejected. Being independent meant being helpless – he realized how different things were compared to when he worked at Mitsubishi and Ricoh. Having left the bank, exhausted, a branch of Daiwa Bank caught his eye. He decided to try his luck there on a whim, but to his surprise, the branch manager himself came to him, listened to what he had to say, and agreed to open an account. When one door closes, another one opens. Shindo learned that he should not disregard people’s compassion.

On the other hand, he was still unable to rent an office. He had to move from one community center to another, and was technically unemployed. After three months, he found an office, and MegaChips was finally up and running.

The first job came from Shindo’s personal connections. Nihon Kokan (NKK, now JFE Steel) outsourced LSI development to MegaChips. A former boss of Shindo’s at Ricoh had been assigned as an advisor to Nihon Kokan, and he passed the offer on to MegaChips.

Later, Shindo was asked to serve as a teacher for Nihon Kokan’s semiconductor business launch and to help transfer technology. Not one to leave another’s compassion go unanswered, Shindo headed for Nihon Kokan. His title became Deputy General Manager of the Electronic Devices Division. He left MegaChips in the hands of his subordinates, who traveled around the country energetically, securing one job after the other. The company grew in size, achieving sales of 500 million yen and and ordinary income of 28 million yen with only 24 employees. MegaChips seemed to have gotten off to a reasonable start since its establishment. However, their winter was just around the corner. In 1991, the bubble economy burst.

Jobs were cancelled one after another. The cash flow was so bad that the company could not afford to pay salaries for the next two to three months.

The company was divided between two opinions: to continue on the path of self-reliance, or to become an affiliate of some big company. Shindo took all the employees to Arima Onsen and held a debate among them. Shindo himself did not express a single opinion, but let the employees come to their own conclusions. As a result, the decision was made to maintain independence. (Unfortunately, some of the employees resigned after this meeting.)

MegaChips’ employees then resumed their desperate search for orders. They were open about the company’s plight, and went around seeking work. Thanks to their efforts, the company was able to maintain sales of 1.1 billion yen and ordinary income of 28 million yen in its second fiscal year.

At this time, Shindo was a director of MegaChips, but not the president. His position as Deputy Manager of Nihon Kokan’s Semiconductor Affairs Department was still his main job. Now, he had to take care of their troubles as well.

NKK was better known than MegaChips, but when it came to semiconductors, they were completely obscure. Shindo had to use his own personal contacts to get orders.

He visited Nintendo, a company that he had once taken on a job for. At the time, Nintendo, which was making the Super Famicom (SNES), had a shortage of mask ROMs (cassettes) to store games, and orders were being placed with factories all over Japan. The Nintendo representative who interviewed Shindo said to him:

“If you say you can do it, we’ll place the order. You have helped us in the past, and we know you are capable. Now that you have started your own company, grit your teeth and do your best.”

Thus, Shindo had managed to find work far more easily than expected. They subsequently received an order for mask ROMs for the Super Famicom. Moreover, this was not simply a design-only job, like Shindo had been doing up to that point. They had to actually manufacture the mask ROMs and deliver them to Nintendo. MegaChips did not have a factory, and the Nihon Kokan plant was not yet in operation at this point. This was a much bigger job than anything they had done before.

Shindo had an idea about which factory to use – VTI, a company he had worked with when he was in the United States. Miin Wu, the founder of VTI, had returned to Taiwan after VTI’s success and established a semiconductor manufacturing plant, Macronix. Miin Wu welcomed Shindo with open arms when he brought him the Nintendo job. The contract was unbelievable.

The terms were overwhelmingly unfavorable to Macronix: payment was to be made 30 days after inspection, the deal was in yen, and included a production capacity guarantee. The reason for this was that MegaChips did not have the funds to establish the L/C (letter of credit) required for international transactions.

However, Macronix accepted these conditions.

“We have known you for many years and have sufficient trust in you. VTI’s success is the result of your cooperation. It is our turn to support you. We will accept the conditions. Let’s cooperate and grow together.”

Miin Wu shook hands with Shindo. Human compassion and connection are truly not to be taken for granted. MegaChips took another leap forward.

In 1993, Shindo completed his work at Nihon Kokan and returned to MegaChips. At that time, Nintendo also transferred all orders for Nihon Kokan’s mask ROMs to Shindo’s side, MegaChips. Nintendo was not ordering mask ROMs from Nihon Kokan, but from Shindo personally. The mask ROMs that had been ordered separately from Nihon Kokan and MegaChips were consolidated into a single order and sent over to MegaChips. Their development accelerated.

In 1994, MegaChips deepened its partnership with Macronix. The company obtained exclusive rights to sell mask ROMs for Nintendo. This was practically synonymous with obtaining the exclusive rights to Taiwan-made mask ROMs for Nintendo.

The development commissioned by Nintendo was not limited to mask ROMs. They asked Shindo, who had created the LSI for the Famicom, to redesign the main LSI for the next-generation Nintendo 64. The development team from Nintendo, as well as personnel from Macronix, were brought in and joint development continued. MegaChips put all its effort into selecting a CPU, developing a clock generator for Rambus memory, and developing a large-capacity, low-cost mask ROM. The project was accepted by Nintendo. MegaChips succeeded in achieving vertically integrated development and design, including architecture and production technology, rather than just outsourced production. After discussions among Nintendo, MegaChips, and Macronix, a contract was signed for the integrated production of mask ROMs. This meant that mask ROMs would go through Macronix (although some software for Nintendo DS and Nintendo Switch is made by other companies).

Nintendo was satisfied with this success as well, and continued to outsource the development of its major LSIs to MegaChips. The custom LSIs for the Game Boy Advance and GameCube were designed by MegaChips and produced by Macronix. The same is true for the Game Boy Advance mask ROMs, and the custom LSIs for the Wii and Wii U. The Wii U uses a specialized LSI for wireless low-latency video compression and decompression processing. The current Switch also incorporates an LSI designed by MegaChips, and Macronix is the primary manufacturer of game cards for the Switch.

The genius who created the Famicom was again involved with Nintendo in a different way, and ended up forming the foundations for Nintendo’s hardware. Nintendo had unconventional ideas that did not rely on the usual assumptions. The technical capabilities that supported these ideas were kept together by human compassion and connection. If Nintendo had turned away Shindo, who had already quit Ricoh, if the branch manager of Daiwa Bank had not opened the account, if Shindo’s former boss had not given the job to MegaChips… if any of these connections had been severed, the current game market would be in a very different shape.