This article is a translation of the work of Syosin Kai, a Japanese researcher of the history of Japan’s game industry. Translation and publication are being done with written permission from the author. We thank Syosin Kai for his contribution.

Please enjoy this article with the following disclaimers in mind:

- This article was written by a person unaffiliated with the industry, based on industry publications from the period in question

- The said publications include many inconsistencies, so some claims do not have conclusive evidence

- Certain publications this article was based on were in later years identified by industry persons as containing inaccuracies

Who is the first person that comes to mind when you hear the words “CEO of Nintendo”?

While Shuntaro Furukawa currently holds the title, there are surely many whose minds first travel to Satoru Iwata, who became etched into our memories during his long run as the face of Nintendo Direct. On the other hand, gamers with a few more years of experience under their belts may first think of the late Hiroshi Yamauchi, who nurtured Nintendo into a world-class company with the NES.

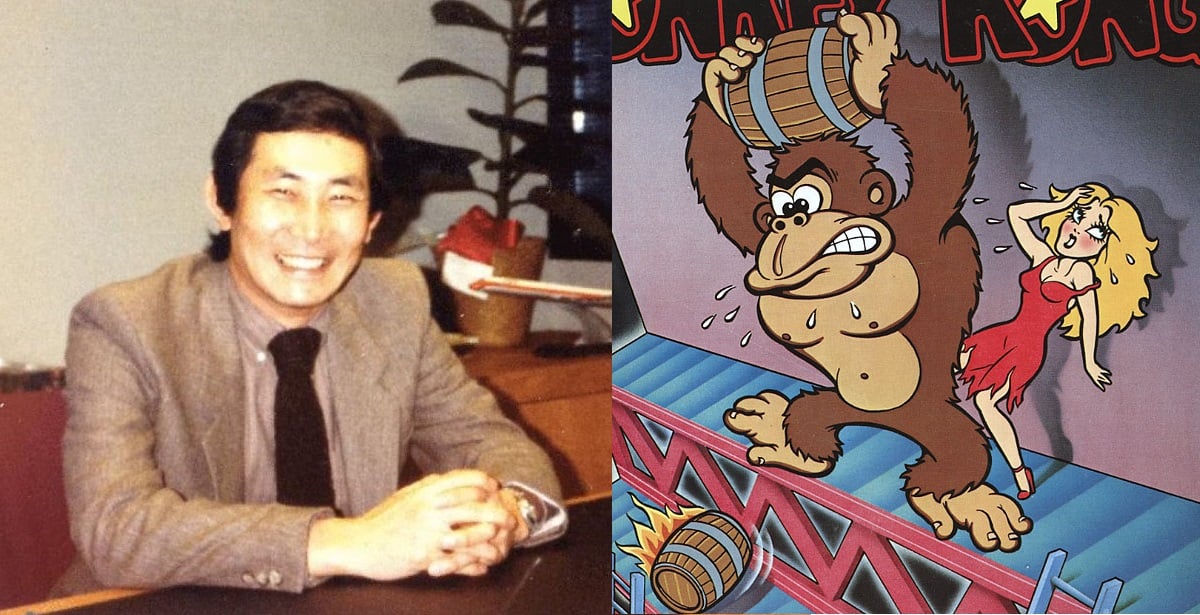

However, there is one man who never managed to carve his name into this hall of fame – Minoru Arakawa. Arakawa served as President of Nintendo of America for many years, playing a key role in Nintendo’s transition from a Japanese company to a global force. He was expected by many to become the next CEO of Nintendo and was trusted deeply by Hiroshi Yamauchi. But why, despite his skills as a businessman and the trust he had earned, did Arakawa never become CEO? I took a deep dive into his life and career to find out.

Minoru Arakawa was born in Kyoto. His father ran a generational textile business, and his mother was a descendant of the 59th Emperor of Japan. His maternal grandfather was an influential member of the Japanese Diet, while his great-grandfather served as the first mayor of Kyoto. Needless to say, the Arakawa family was one of the most prestigious families in Japan, and the young Minoru was taught to always bear in mind the responsibility that comes with carrying the Arakawa name. As Minoru was the younger son, he was not expected to inherit the family business – his older brother had taken care of things. But what was Minoru to do then?

He graduated from Kyoto University in 1968 with no clear goals in sight. His family was so wealthy that he did not need to work, but that in itself was a difficult position to be in. Pondering what he was supposed to be doing, Minoru finally decided to leave the comfort of his parents’ home and travel abroad in search of answers.

Flying to the United States, Arakawa enrolled at MIT (Massachusetts Institute of Technology). One day during his studies, he met a group of young Japanese businessmen who were visiting the United States. They boasted of their position that allowed them to do business all over the world. This left a strong impression on Arakawa, who from that point began aspiring to join a trading company.

After graduating from MIT and returning to Japan, he decided to join the Japanese trading company Marubeni Corporation. Marubeni was involved in the construction of hotels and buildings around the world. This made Arakawa, who had studied civil engineering at MIT and Kyoto University, a perfect match for them.

In 1972, after deciding to join Marubeni, Arakawa fell in love with a woman. Her name was Yoko Yamauchi, and she was the daughter of Nintendo’s CEO Hiroshi Yamauchi. The two first met at a party and immediately developed feelings for each other. However, their relationship faced an obstacle – Hiroshi Yamauchi had an aversion towards high-class families, making marriage a precarious topic to bring up.

Arakawa’s family was conservative, with a long history and wealthy roots. On the other hand, the Yamauchi family was of a lower rank, and whatever wealth they owned was earned by Hiroshi during his lifetime. Residing in Kyoto, Hiroshi Yamauchi inevitably crossed paths with such families while doing business, but on these occasions, he was clearly looked down upon, inflicting on him something of an inferiority complex.

Overcoming multiple obstacles, the young Yoko managed to arrange for her father to meet Arakawa with the help of her mother. Thus, he was invited to dinner with the Yamauchis. Unexpectedly, Hiroshi told him,

“If you intend to marry my daughter, do so quickly.”

Minoru Arakawa’s calm and sincere attitude had won over Hiroshi. The marriage took place six months later, with a lavish reception at the Heian Shrine in Kyoto.

After his marriage, Arakawa led a busy life.

A large condominium was to be built in Vancouver, and Marubeni chose Arakawa to take charge. He flew to Canada with his wife and children. At this point, he held no interest in his father-in-law’s video game business.

Then, it came – an invitation. Nintendo was planning to build a manufacturing plant in Malaysia, and Yamauchi asked Arakawa to go and work there as the factory’s manager. Arakawa was not keen on the idea, and his wife Yoko was against the two working together, which resulted in the plan ultimately falling through.

However, it didn’t take long for another invitation to come from Yamauchi. This time, he wanted to entrust Arakawa with establishing a subsidiary in the US.

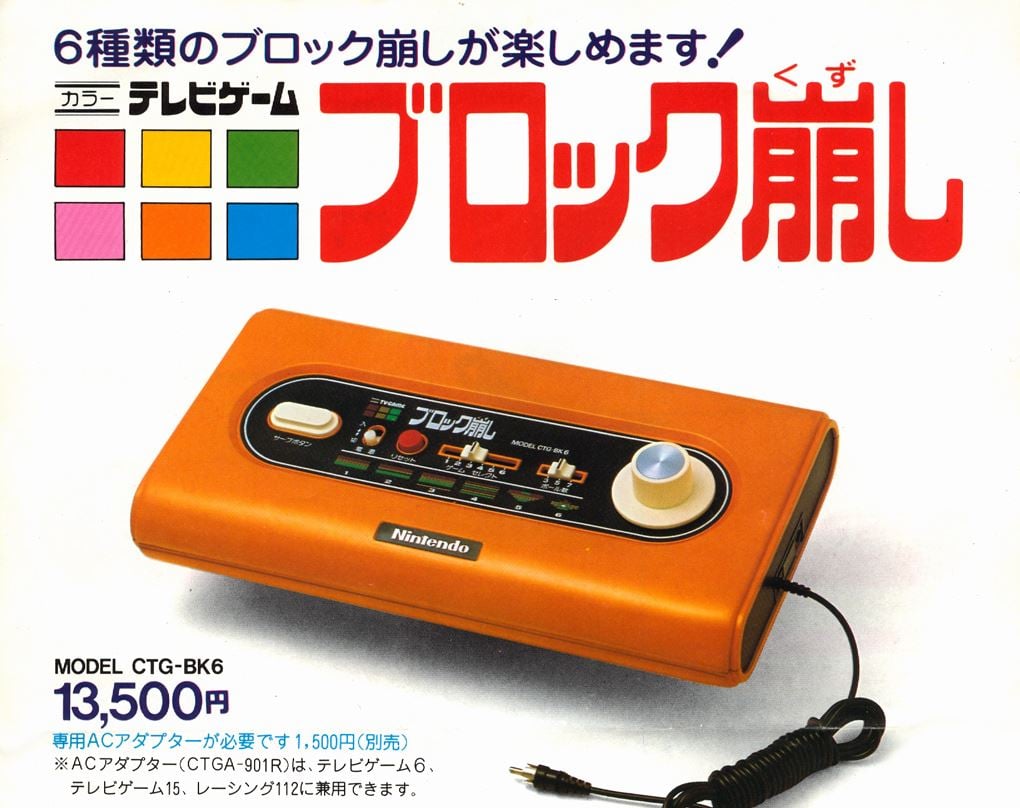

In the early 1980s, before the launch of the Game & Watch, Nintendo was predominantly focused on developing consoles (which had achieved significant sales with the TV Game 15/6) and arcade games – and the US was the birthplace of arcade games. Nintendo wanted to get into the US market at any cost, however, Hiroshi Yamauchi himself was not proficient in English and had a hard time flying, making it difficult for him to make regular roundtrips between Japan and the US. Therefore, his son-in-law, who was already working overseas, was the perfect candidate for the job. Yamauchi didn’t want a worker bee to send abroad, but an entrepreneur willing to spend his entire life there, and he saw that potential in Arakawa.

Yamauchi took to persuading his son-in-law, explaining his ambition and passion at length.

Arakawa was tempted, but decided to hold off on responding. He could not give an answer without consulting his wife first. Yoko was initially against the idea, but soon relented. She could tell that her adventure-hungry husband already had his sights set on something new. Arakawa, on the other hand, was enticed by the idea of entering the completely unknown field of video games and growing his father-in-law’s company.

He accepted Yamauchi’s offer, and thus became President of Nintendo of America (NOA).

Arakawa flew to New York and rented an office. Yoko became his secretary and took on the task of managing the office, which was small and dingy. As there was no money to renovate it, the two did what they could on their own. Yoko was eager to support her husband to the best of her ability.

Arakawa’s mission was to break into the American market. But first, he had to get familiar with games. He had never played a video game in his life. Thus, he started visiting local arcades and observing young people. He tried to get a sense of what a good game was based on how players were reacting to it – a method his father-in-law, Hiroshi Yamauchi, would also come to use in later years. When he judged the quality of a NES game, he did not evaluate it by his own playing experience, but by the reactions of others playing the game.

From there, Arakawa started hiring young men he met at arcades to help with transport. Together (Arakawa and Yoko included) they would carry shipments of Nintendo arcade game cabinets into the warehouse and deliver them to suppliers.

The US arcade game market was booming. Following in the footsteps of Space Invaders, Pac-Man was consistently pulling quarters out of young people’s wallets. Atari launched Chuck E. Cheese’s Pizza Time Theater, captivating children with its combination of arcade, pizza, and theme-park entertainment. Driven by the market’s vigor, Nintendo arcade games sold by NOA were performing well.

However, midway through the year 1980, dark clouds appeared on the horizon. Game sales began to decline, and the entire industry fell into a recession. NOA’s performance was just as sluggish.

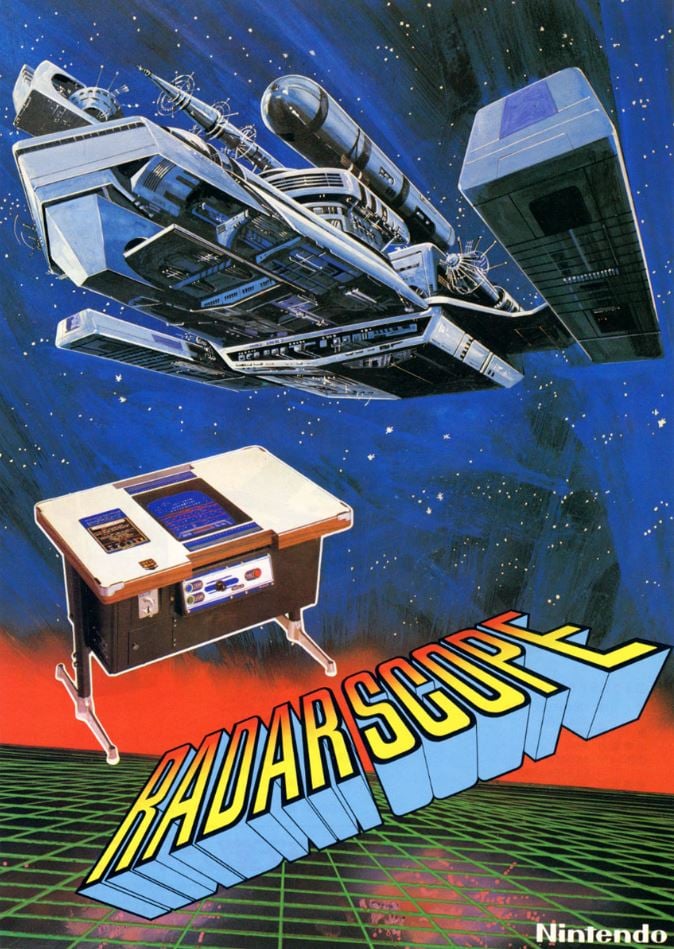

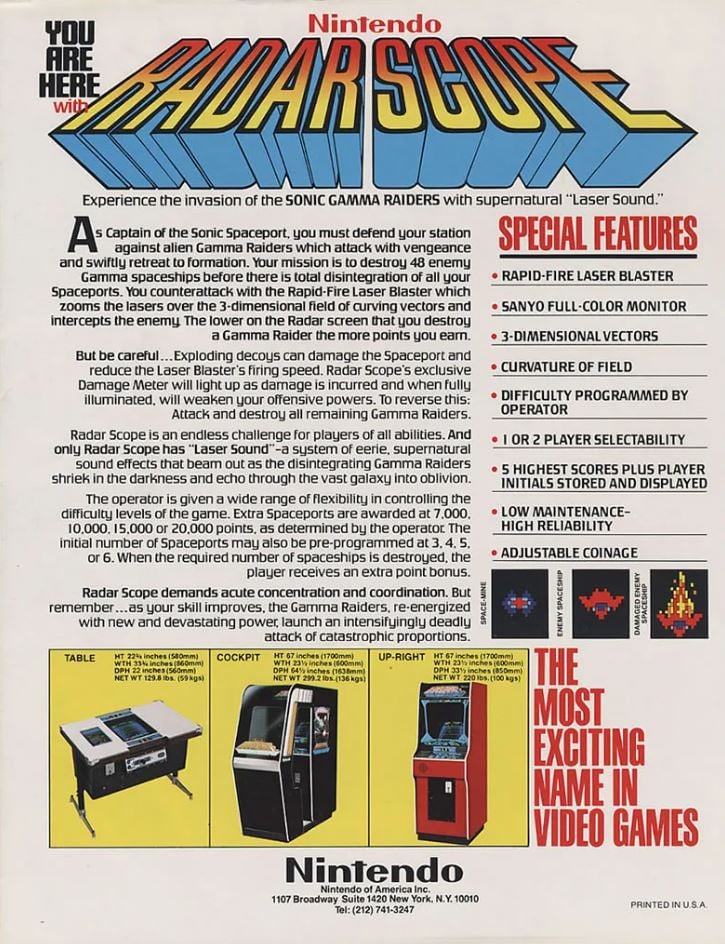

Arakawa decided to take a gamble. Instead of placing small bets on a variety of games, he decided to go all in on one title and aim for a breakaway hit. He carefully evaluated the games sent by headquarters and chose one – Radar Scope. It was a simple shooting game, but its samples had earned positive responses in Seattle. It was all or nothing. Arakawa ordered 3,000 Radar Scope cabinets from HQ. It was a huge investment that cost NOA almost all of its assets.

However, Arakawa made a mistake. To cut down on transportation costs, he placed the order by sea. It took four months to reach the US East Coast from Japan. By the time the Radar Scope cabinets arrived, it was already an outdated game. It no longer enjoyed positive reception, and became an unsellable product. The Radar Scope cabinets placed in arcades saw no quarters.

Arakawa panicked. He was now fully aware of just how unforgiving the video game industry was. He’d managed to sell 1,000 units, but there were still 2,000 large arcade machines sitting in the warehouse, going nowhere.

Knowing he couldn’t keep quiet about that was happening, Arakawa begrudgingly came clean to Yamauchi about his predicament. His father-in-law was furious.

However, things couldn’t just end there, and they both knew shouting at each other wouldn’t improve the situation. Arakawa tried to come up with a solution. He thought of selling the game cabinets by replacing the chip inside with a new game. He would have Nintendo develop and send over a new game to him, repaint the cabinets, and sell them as new games. He pleaded with Yamauchi to give the strategy a chance. His father-in-law still had some anger left to vent at him, but ultimately, Yamauchi decided to give Arakawa a chance. He agreed to start up a new game project.

An unknown newcomer was selected for the job. His name was Shigeru Miyamoto, who would one day be known to the whole world for his games.

Arakawa did not just sit idly and wait for the new game to arrive. Setting up his office in New York had been a mistake, he came to realize. If he was going to have games sent from Japan, he should have gone to the West Coast instead of the East Coast. Based on average shipping times, he decided to relocate to Seattle. It was on the West Coast so Cargo from Japan could arrive in just two weeks.

He asked Phil Rogers, an old friend from his Marubeni days, to help him find a new warehouse and office. He was introduced to a rental warehouse in Segale Business Park, run by Mario Segale. It included an office and was 5,000 square meters in size. Arakawa decided to rent the space and brought in all his belongings by rail, the mountain of Radar Scope arcade machines included.

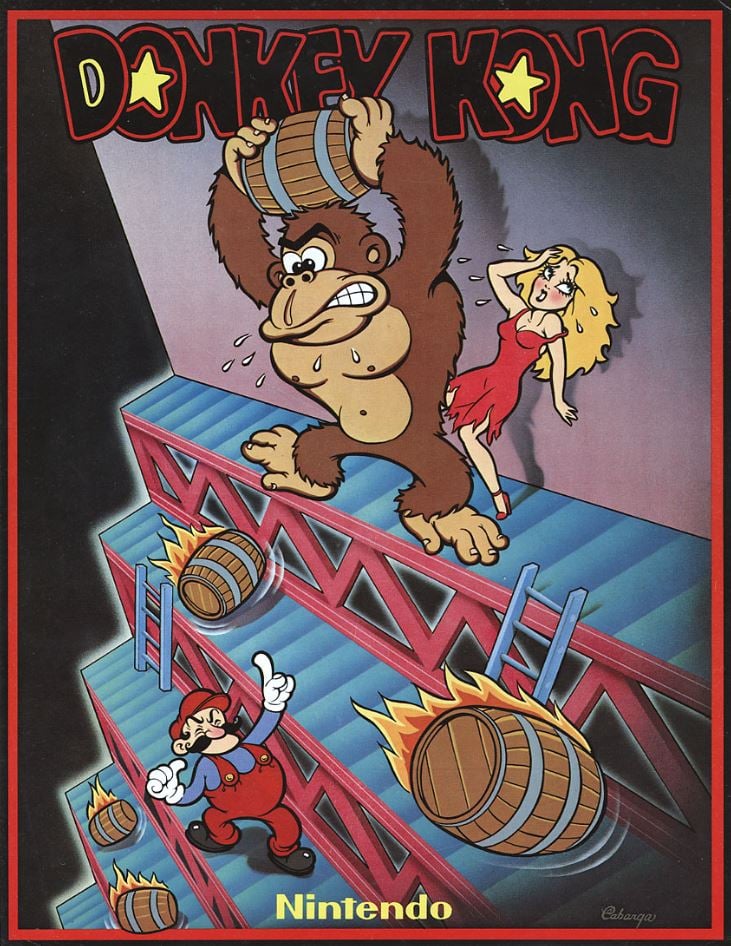

Then it arrived – the long-awaited and dearly anticipated new game. Everyone at NOA gathered in the warehouse and huddled around a game cabinet. A technician carefully attached the chip to Radar Scope’s board and launched the game. The title screen read “DONKEY KONG.”

It felt like a completely meaningless title, but Arakawa had to make it sell. He set about altering Radar Scope arcade machines into Donkey Kong machines. He modified the cabinet and added a brief description with rules. Something had to be done about the characters’ names too. In the initial proposal, the protagonist was named “Mr. Video,” and the princess was simply “Lady,” which felt bland. Ultimately, it was decided that Lady would be renamed “Pauline” and the protagonist “Mario,” in honor of the warehouse’s owner Mario Segale.

The new Donkey Kong sample was placed in a bar located near NOA’s office, and sales exploded from day one. Could this be it? Arakawa felt definite promise in Donkey Kong.

When the rest of the parts needed for Donkey Kong arrived from Japan, Arakawa and his team got to work on modifying the remaining machines, and the game was soon being shipped across the US. It brought in piles of quarters from all over the country. Nintendo had succeeded in creating a hit on par with Pac-Man.

Arakawa poured all of his energy into Donkey Kong. As a result, the 2,000 units of what was once dead stock sold out in no time. He frantically called headquarters. “Send more Donkey Kong, quickly! Thousands of units!” By this time, Donkey Kong was already growing popular in Japan as well. A good game knows no borders – Space Invaders and Pac-Man had likewise become hits in both the US and Japan.

Preparations were made to start mass producing Donkey Kong.Arakawa had to secure more staff. There were not enough salespeople at NOA, and they were understaffed in assembly too. The company, which only had two employees at its founding, quickly grew to 125 people. Donkey Kong was being shipped at an astonishingly quick pace – 250 units per day. Cumulative sales of the new title reached 60,000 units. In only its second year since founding, NOA saw 100 million dollars in sales, an unprecedented growth.

In 1982, Donkey Kong Fever was spreading across the entire United States, but at the same time, an unavoidable problem started to emerge – piracy. Clone games made to resemble the original (much like Nintendo’s Space Invaders clone “Space Fever”) were one thing, but the pirated versions of Donkey Kong entering the market were exact copies. Half of the Donkey Kong machines in circulation at the time were pirated versions.

This is where another important figure steps in – Howard Lincoln, a lawyer who had connections to NOA. Lincoln set about tackling the piracy issue. He hired detectives, mobilized the police, and even got the FBI involved in his efforts to eradicate piracy. Considering that the pirate copies were being distributed on such a large scale, Lincoln believed that the mafia must be involved.

Before long, NOA began to file countless lawsuits against individuals and companies dealing pirated copies of their game. Nevertheless, piracy did not cease. But NOA was gaining more and more experience in litigation and becoming more knowledgeable about trials. Howard Lincoln became close to Arakawa on a personal level and went on to officially join NOA.

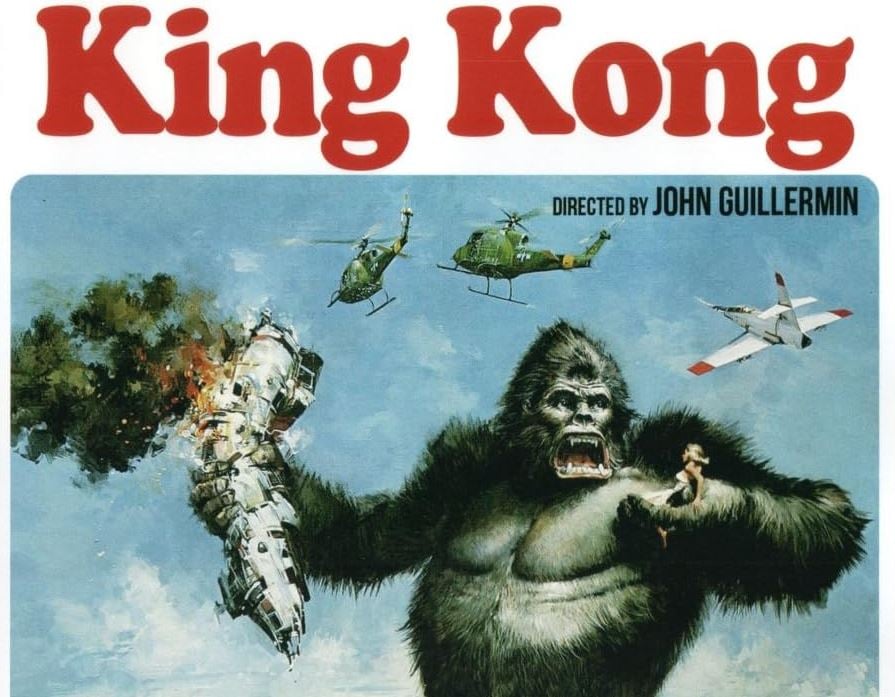

As NOA continued to press on with the lawsuits, it was suddenly attacked from an unexpected direction. After being the plaintiff in so many cases, NOA was now the defendant, facing a lawsuit lodged against them. The plaintiff was none other than MCA (Universal City Studios), the company that owned King Kong. MCA claimed the following:

“Donkey Kong unjustly infringes on the copyright of our company’s motion picture, King Kong. Within 48 hours, NOA must hand over all profits made from Donkey Kong to MCA and destroy the remaining copies of the game.”

In an attempt to find a way out of this predicament, Arakawa consulted with Lincoln, and together they headed to MCA.

As the two listened to MCA’s endless claims, Lincoln remained calm, sensing something was wrong. They left without making any statements.

Arakawa was anxious to resolve the matter as quickly as possible, and Yamauchi also wanted to settle if all it took was playing a couple of hundred million yen. But Lincoln resisted. “We can win. We mustn’t back down,” he persuaded Arakawa.

Sometime after that, the two of them went to see MCA’s CEO and president Sheinberg, an overwhelmingly influential figure in Hollywood. MCA was involved not only in film, but in television, records, publishing, theme parks – you name it. They were a massive conglomerate and definitely not an opponent that could be defeated in a head-on battle. President Sheinberg welcomed the two.

Behind this was, perhaps, his own interest in somehow breaking into the game market. King Kong seemed to offer the kind of compelling justification needed to make a case for tackling Donkey Kong as a product.

However, NOA’s Lincoln said, “We have no intention of settling,” infuriating Sheinberg.

He acted immediately, filing a suit against NOA in New York. Lincoln also flew to New York, as he knew exactly the man who could fight for their case. Belonging to Mudge Rose Guthrie Alexander & Ferdon, he was one of the leading civil suit lawyers in America, a lawyer who would stop at nothing to defend his clients.

His name was John Kirby. He was the man who brought victory to Nintendo.

Lincoln and Kirby flew to Japan. They had to report to President Yamauchi on the lawsuit and collect evidence of Donkey Kong’s development being uninfluenced by King Kong. They interviewed Shigeru Miyamoto and his mentor Gunpei Yokoi and copied their development notes. Yamauchi did not engage in small talk, and the conversation ended with exchanging opinions on the lawsuit.

While the case was in motion, Lincoln was formally invited by Arakawa to join NOA. Lincoln asked to be a manager, rather than a corporate lawyer. This response pleased Arakawa. Lincoln became NOA’s No. 2, the Vice President of Legal Affairs.

The trial finally began. Shigeru Miyamoto’s statement was submitted. He told the whole story very honestly. He testified that during development, they referred to the gorilla in the game as “King Kong.” To this, he added, “In Japan, big, scary gorillas are called King Kong.” They even played Donkey Kong in the courtroom. The judges’ reaction was in favor of Nintendo. “What on earth is ‘King Kong’ about this?” MCA’s argument was difficult to accept.

Then Kirby dropped the bombshell. He combed through past court records and found the smoking gun – MCA never owned the copyright to King Kong in the first place.

In 1975, MCA sued RKO, the company that produced the original black-and-white film “King Kong,” over the rights to remake the film. As King Kong was made in 1933, MCA’s argument was that the copyright had already expired, making the film public domain. “King Kong belongs to nobody” – This argument prevailed, and MCA won the case. In other words, MCA acknowledged that King Kong was in the public domain and “didn’t belong to anyone.”

The situation was overturned in an instant. The enterprise that filed a lawsuit claiming that their rights had been infringed had no rights whatsoever. Moreover, MCA threatened lawsuits left and right to extort settlement money. A company with no legitimate rights, using litigation to greedily seize profits. MCA’s reputation inevitably took a blow.

Their brazenness drew the ire of the judge, who declared that any company that was asked by MCA to stop using King Kong-related materials, or paid a licensing fee had the right to have that money refunded, plus a royalty.

Things got even more complicated from there. It was discovered that MCA had given Tiger Electronics a license to make a King Kong game, which looked exactly like Donkey Kong, for all intents and purposes. Had Nintendo lost the case against MCA, only Tiger’s King Kong would have been able to exist as a legitimate product. However, the judge ruled that this King Kong game was a “malicious copy.” As a result, MCA, the plaintiff, ended up having to pay royalties to Nintendo.

Nintendo was awarded $1.8 million in damages. Howard Lincoln was promoted to senior vice president and general counsel of NOA. Nintendo sent a huge yacht to Attorney Kirby. The $30,000 yacht was named “Donkey Kong,” and Kirby was given the “exclusive naming rights to use for the yacht.” Kirby’s name reverberated throughout Nintendo, and in later years, it was borrowed for the title “Kirby of the Stars” (or Kirby’s Dream Land, as it’s known in English).

References:

Nikkei Business, January 31, 2000, “Business Strategy – Marketing: Nintendo of America”

Nikkei Business, December 21-28, 1998, “Focus Person: Minoru Arakawa”

Ritsumeikan University, College of Image Arts and Sciences, Thesis: “A Comparative Case Study of the Formation of Dedicated Home Video Game Platforms in the Formative Period of the North American Digital Game Industry” – Focusing on ATARI.inc and Nintendo of America Inc. – by Akinori Nakamura

Game Over by David Jeff

The Famicom and Its Era by Masayuki Uemura

Console Wars, Volumes 1 and 2 by Blake J. Harris

Super Mario: How Nintendo Conquered America by Jeff Ryan

Wow this was a good read!

Would love to read something like this regarding CAPCOM’s Tsujimoto