Hi, I’m Nununu, a Japanese game designer making a humble living in a corner of the industry. Thanks to AUTOMATON for giving me a place to ramble about game design. The plan is to look at games – famous hits and hidden gems alike – and break down interesting design decisions that make them entertaining.

For this first volume of the series, I’m focusing on how games start. Specifically, a classic technique for getting players started called gating.

Let’s begin with one of the all-time greats: Dragon Quest I. The opening sequence of Dragon Quest I was developed after much trial and error.

Locking the player in the King’s room

Here’s the very first playable area in Dragon Quest I.

You’ve got the hero, the King, and a couple of soldiers. There’s also a door and some treasure chests – it’s a small room, but it’s packed with points of interest. However, the door is locked. The game won’t let you leave just yet.

When players realize they’re trapped, their natural instinct is to explore their surroundings. They’ll likely try talking to the king and the soldiers.

Once they’ve obtained information they can use, they’ll probably move on to checking the chests. The nearby chests yield 120 gold and a torch – nice, but not what you need to get out of the room. A little farther away is another chest which, when investigated, will finally provide you with the key.

Placing the chest with the exit item farther away from the player is a clever touch. It’s designed so most players will get the key last. It’s a technique meant to build anticipation for a reward, delaying it to make the moment more satisfying. Not only that, but by the time they’ve unlocked the door, players will have already grasped basic knowledge of the game and how it’s played.

By narrowing the player’s range of movement through gating, the game guides them to progress exactly as intended. This is of course, no coincidence – Yuji Horii deliberately designed Dragon Quest I this way.

This “lock the player in the king’s room” approach wasn’t invented out of nowhere either – it was a solution that came from addressing problems revealed through repeated playtests. The process is described at long in this article by Denfaminicogamer.

When you look at this design solution now, you might think, “What, that’s it? That’s obvious.” But it’s not obvious at all. This kind of idea that “solves multiple problems at once” is not something you can come up with easily – it takes the kind of skill that comes from doing intensive problem-solving on a regular basis.

Now that we understand the power of gating, let’s look at some examples of how it appears in other games.

The many examples of gating

The first example is, of course, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (BotW), the game that introduced an open-world system to the Zelda series and propelled its popularity to even greater heights.

While there’s a lot to discuss about BotW’s game design, as mentioned – I will be focusing on how it starts.

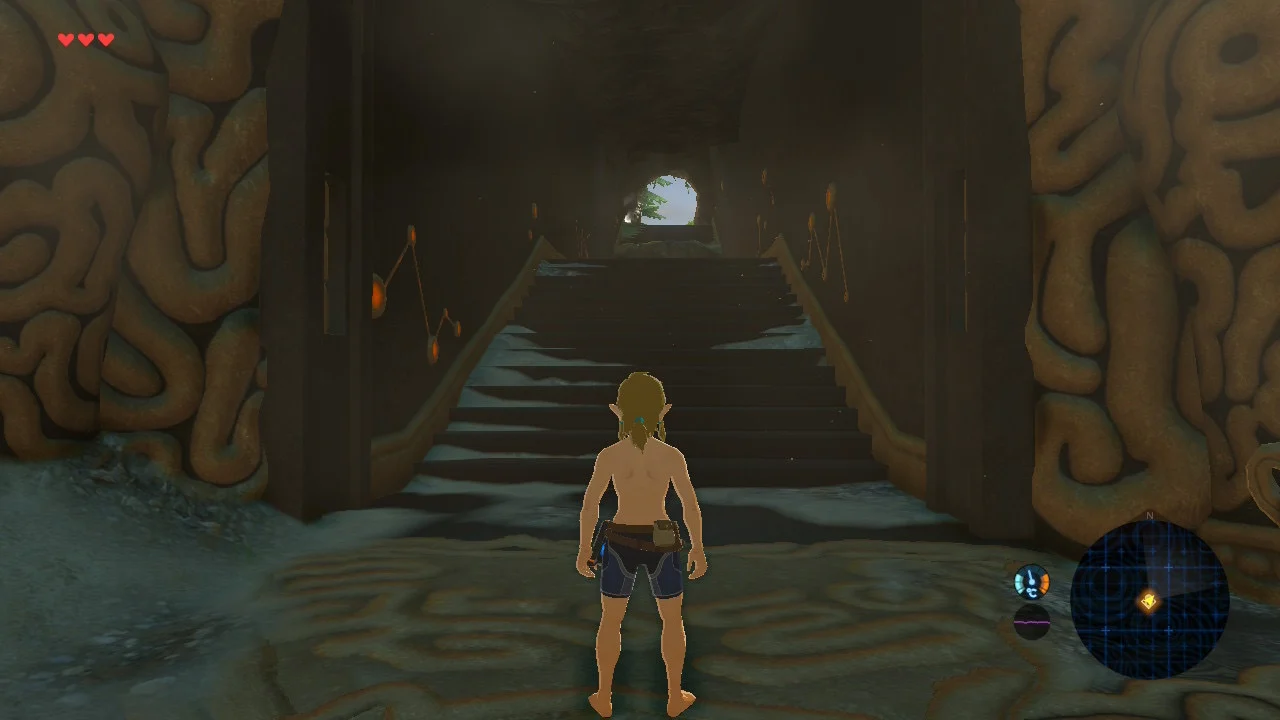

When Link wakes up, he finds himself trapped in a cave. Here it is again – gating. By limiting the player’s actions, the game teaches its basic rules: blue glowing objects advance the game, treasure chests yield useful items, and so on. It’s a textbook example of gating.

Even Link’s half-naked state at the start of the game is intentional and part of teaching the player. The half-naked look is unflattering, and it makes you feel sorry for the poor guy. Naturally, you’ll want to equip him with clothes. The first chests you open give you pants and a shirt, improving both Link’s appearance and defense.

Near the cave exit is a small cliff you can’t jump over. So you go, “What do I do…Oh, right, why don’t I climb.” One of BotW’s biggest innovations compared to prior open-world games is that it lets you climb anywhere. The terrain design here teaches that mechanic naturally and with subtlety.

As a fellow game designer, I was blown away when I first played this. It’s the kind of solution you can only arrive at if you’re very conscious about “what you want to communicate to the player.” It’s not thinking just “What do I want them to learn?” but “What do I want to convey?”

There’s more, though. When designing games, how do you create a good learning experience? By giving a reward. While learning itself constitutes growth and feels good on its own, adding a tangible reward makes it even better. Challenges should come with rewards – it’s a fundamental principle of game design.

So, what’s the reward waiting at top of that first cliff in BotW?

The answer is… the world.

Here, you get your first look at the vast world you’re about to traverse.

In the first place, what is it that people who bought BotW expect from the game? It’s the promise of exploring a huge, unknown world. And the designers throw it at you right at the beginning. It’s truly brilliant game design.

Here are some other examples:

In the first Dark Souls, you’re locked in a cell right from the start. You have to find a key and open a locked door, just like Dragon Quest 1.

But even after you’ve found your way out of the cell, you have to pass through a series of enclosed corridors and spaces, learning the game’s fundamentals along the way. In other words, the gated areas are strung together. Connecting these kinds of spaces is a common tutorial technique.

Another example is The Last Guardian. A boy wakes up to find himself trapped among ancient ruins with a giant beast named Trico. On his own, he can’t escape. He has to rely on the mysterious beast’s powers to get out. This is another great use of gating.

The three basic types of gating

Finally, let me offer a little nugget of wisdom to broaden your thinking about gating. If we strip the concept down to its core, it’s about restriction. It’s any situation where, as a player, your actions or abilities are limited.

I believe gating can be divided into three basic categories: physical, ability-based, and mental.

Physical Gates: Hard barriers like locked doors or walls you can’t break down (Dragon Quest I, Dark Souls).

Ability Gates: Common in Metroidvanias – you can’t reach somewhere by just jumping, or a passage is too narrow to crawl through. But once you gain the right ability, you can overcome the obstacle.

Mental Gates: Best seen in TUNIC – it’s not that you can’t do something; you just think you can’t (or the game makes you believe so). For designers who place importance on narrative, this is probably the most satisfying type of gating to pull off.

In the end, it all boils down to restrictions, so you don’t have to think about these separate categories. But having them helps me when brainstorming ideas – after all, the trick to coming up with ideas is to zoom in and out of your picture, narrowing and broadening your perspective. That’s why being able to categorize is useful.

However, you don’t have to strictly stick to these categories. Ultimately, it’s always about two questions: What do you want the restriction to teach? And what do you want it to communicate?

Well, I’ll call it a day here. If you enjoyed reading this, that’s enough for me.