At Japan’s Computer Entertainment Development Conference (CEDEC) held on August 23, Nintendo held a lecture on The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom’s development (as reported by Famitsu). The presentation, given by the dev team’s lead QA engineer, environment programmer and lead terrain designer, focused on how Link’s brand-new Ascend ability was implemented in TotK. It also revealed some interesting insights into what kinds of automated processes were used (and avoided) during the game’s development.

One of the biggest innovations Tears of the Kingdom brought to the Zelda series when compared to its predecessor, Breath of the Wild, was its vertically complex world – featuring aerial, ground and underground levels. The underground level – The Depths, is a system of over 200 caves that each allow a wide range of gameplay, making it one of the biggest additions to the game.

The development teams’ basic workflow when creating TotK’s caves was: Conceptualization > Implementation > Playtesting. Based on the results of playtesting, things would go back to conceptualization, and the cycle would start once again. Going through this cycle multiple times was crucial for raising the game’s entertainment value, according to lead terrain artist Takehara. That’s why, TotK’s team looked to automate parts of the development process in order to increase the number of cycles they could afford to perform.

“However, if we were to pursue this blindly, the game could potentially end up losing something valuable,” he notes. In order to prevent over-automation, the team started out by considering what aspects of the process they must not make automatic.

They decided that level design is at the core of the playing experience, and thus must be done “by hand.” The same goes for asset placement relevant to level design, such as where to put resources and enemy bases. Art too informs gameplay and shapes the playing experience, and thus needed to be overseen by real artists. Therefore, they decided that they would only automate processes that were not related to gameplay.

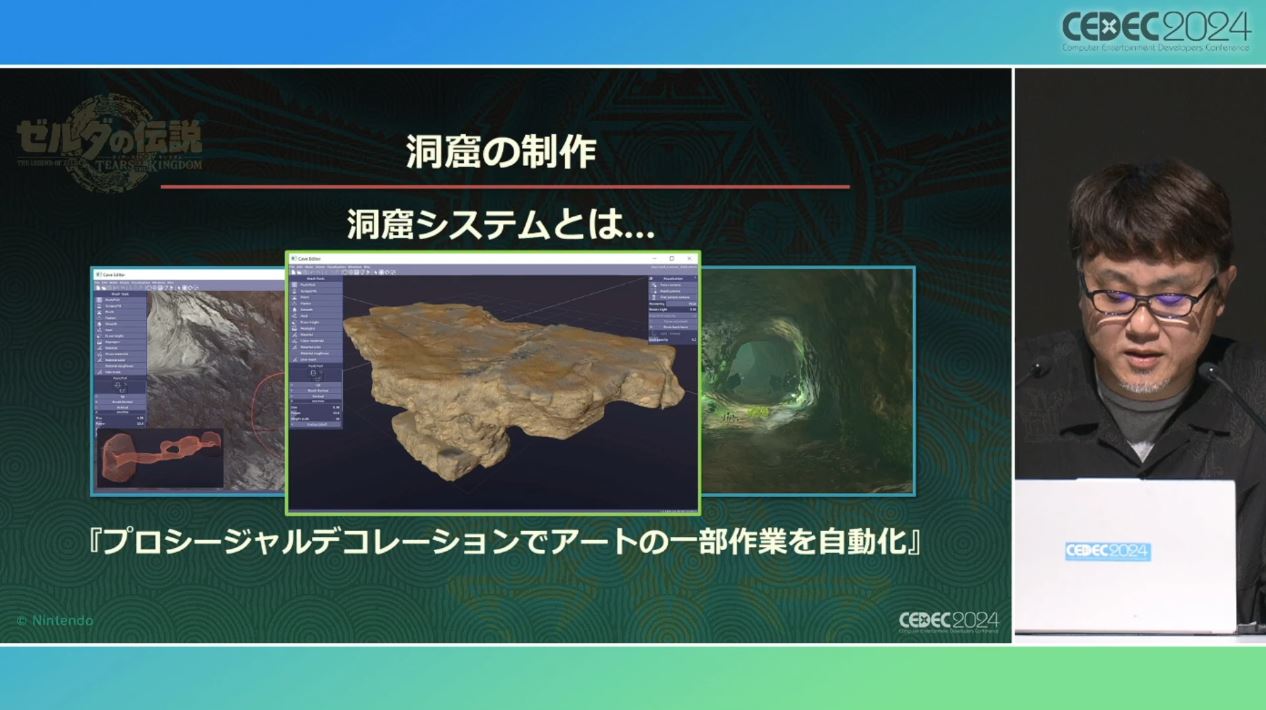

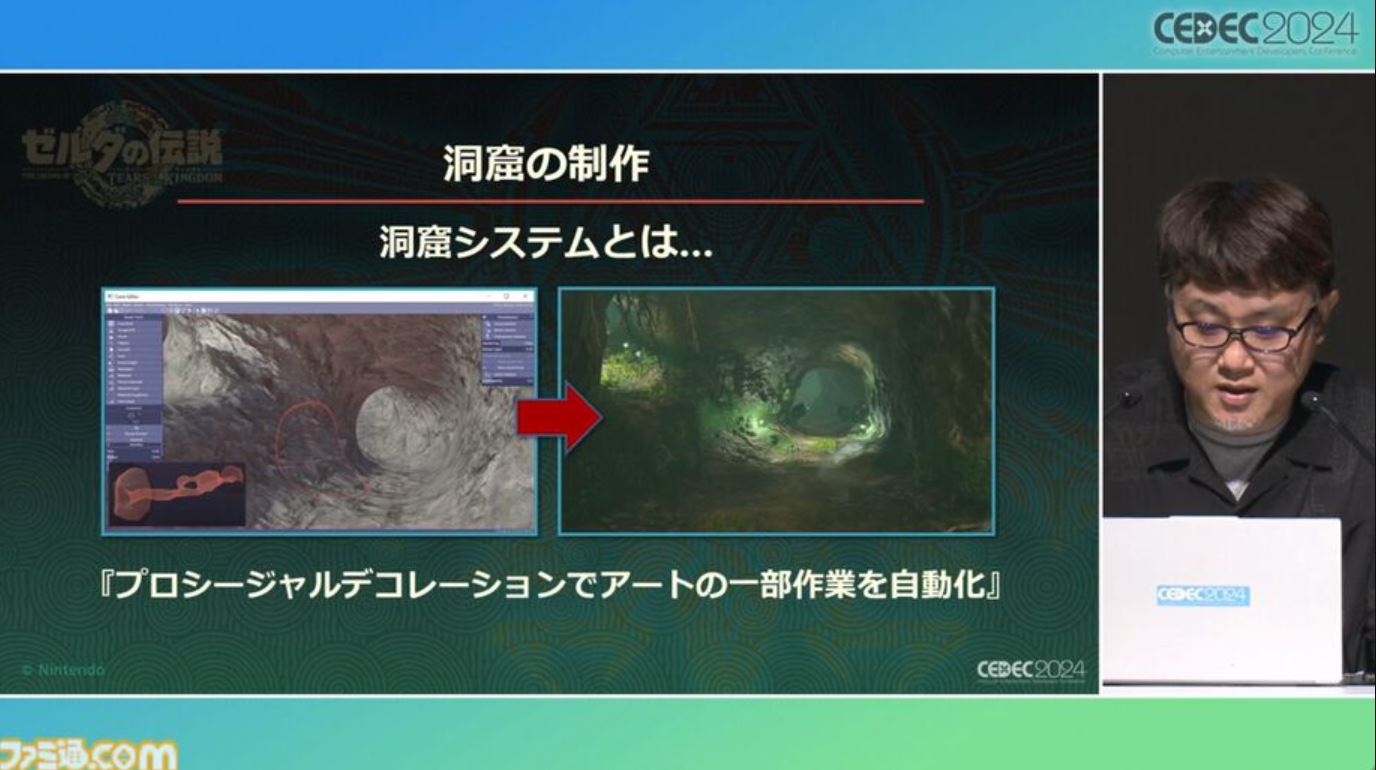

Based on this premise, they formulated the “cave system” – the optimal workflow for creating Totk’s caves. The cave system introduces procedural modelling (controlled by artists) for areas that are “decorative” and do not affect level design.

Before introducing this workflow, in each cycle of “Conceptualization > Implementation > Playtesting,” the team had to first finalize level design/gameplay, and then do manual detailing as a separate process. After this step was complete, it was hard to go back and make gameplay changes, thus slowing down the cycle. However, using procedural modelling, TotK’s team was able to work on both gameplay and art in parallel, without the two processes conflicting with each other. The “cave-system” proved to be so cost-effective that it went on to be implemented not only for caves but for generating stalactites and Sky Islands too.

Interestingly, Takehara also notes that this innovation changed the artists’ mindset. Upon seeing that processes could be automated without losing creativity, they became eager to propose new ideas for further automation, rather than insisting on doing everything manually.