Although Capcom rose to fame as a console game developer during the Famicom (NES) era, establishing itself outside of the arcade game market through hits like Mega Man, this did not necessarily mean they were making a lot of money. Capcom veteran and Street Fighter II producer Yoshiki Okamoto recently discussed this topic on his personal YouTube channel, explaining how hard it was for third party developers like Capcom to turn a profit from making games for the Famicom.

While acknowledging that there may be some exceptions, Okamoto says that aside from Nintendo itself, most companies involved in the production and distribution of Famicom game cartridges 40 years ago didn’t make much of a profit at all (including retailers), despite the console selling 60 million units and creating a huge market.

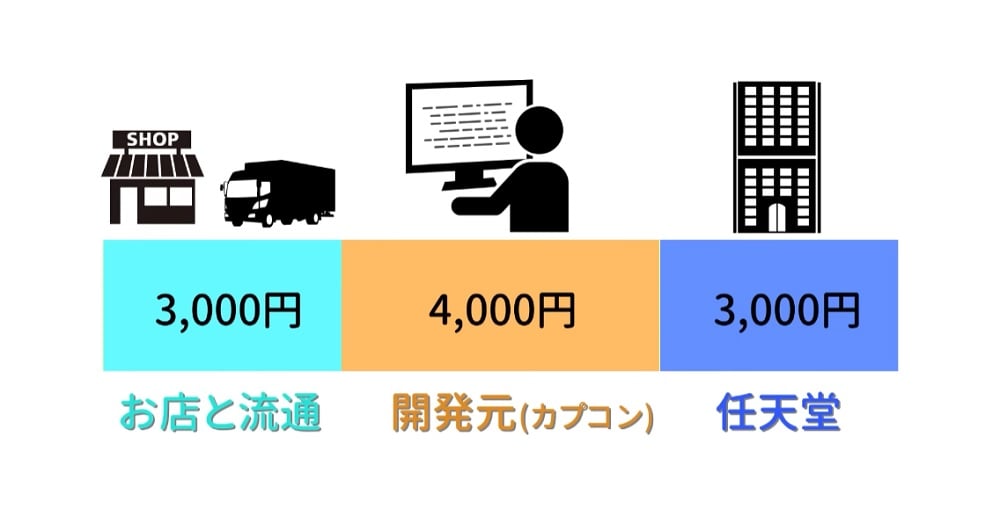

“Let’s say a Famicom cartridge sold for 10,000 yen at retail. Out of that, 3,000 yen went to the retailer. 4,000 yen went to the software developer, like Capcom, and 3,000 yen went to Nintendo. Out of Nintendo’s 3,000 yen share, about 1,500 went to manufacturing contractors. Since Nintendo got paid upfront for the exact number of copies, manufactured the cartridges, and delivered them, what happened after that didn’t matter to them. In other words, only Nintendo had a guaranteed profit,” Okamoto explains.

But for companies like Capcom, who were new in the industry and didn’t have a lot of cash on hand, paying 3,000 yen per unit upfront was a big financial burden. The only solution was to take out bank loans to pay Nintendo. After receiving payment, Nintendo took between 1.5 to 3 months to deliver cartridges. Then, Capcom would send them out to distributors and issue invoices, but instead of getting paid immediately, they’d get a promissory note that would only turn into cash 90 days after a product was sold.

So, between the 3 months it took for production and 3 months of waiting on payment, Capcom would rack up 6 months worth of bank interest. When that interest was combined with development costs, marketing costs and other expenses, the company would, according to Okamoto, be left with a paper-thin profit margin.

Another related issue Okamoto highlights is that of unsold stock. As game cartridges took up to three months to make, developers had to order slightly above estimates, as extra shipments could not make it in time (while the game was still relevant), thus resulting in loss of opportunity if stock happened to run out. This would create the issue of leftover stock that cost the developer a steep 3,000 yen per unit, once again quashing profits.

These kinds of issues, according to Okamoto, are why the release of the PlayStation 1 was so revolutionary for third party developers. “Capcom’s profits skyrocketed with the switch from cartridges to discs,” he comments. The biggest factor was the difference in how Sony handled returns compared to Nintendo.

“Let’s say Capcom paid Sony 1,800 yen per disc. The manufacturing cost of the CD was 200 yen, and the remaining 1600 yen was Sony’s share.” However, if Capcom were to return unsold CDs, Sony would give back the 1600 yen they took as their share, only charging the 200-yen manufacturing cost. Nintendo did not do this, which made leftover stock such a big expense for third parties.

Additionally, Okamoto points out that restocking speed improved drastically with the PlayStation, as Sony was able to deliver extra disc shipments within a week. Thanks to this, developers were able to respond to sudden spikes in interest and “ride the wave” of their titles’ popularity for a longer time, leading to higher profits.

While he circles back to the fact that the Famicom’s cartridge system “really only benefited Nintendo,” Okamoto stresses that the NES and SNES eras were still crucial for Capcom gaining a playerbase and establishing its console game sector.

Related Article: The life and genius of Masahiro Shindo, the secret hero who propped up Nintendo’s console development from the NES through to the Nintendo Switch