Ghostwire: Tokyo is a game full of humor. However, a lot of this humor assumes a certain level of Japanese understanding, along with knowledge of stores and products available in Japan. While there will be people that understand this high-context humor, it will likely be lost on a large number of players that can’t read Japanese. This also may be the reason for the game being assessed differently inside and outside of Japan. As for me (the original author of this article), probably around 90% of what I’ve found interesting about the game is based around these cultural touchstones.

On social media, we can see a number of Japanese players posting bits from the game highlighting what many likely wouldn’t understand without proper context. In this article, we want to highlight some examples of these high-context jokes. The game isn’t just an authentic recreation of Shibuya but is full of parodies and wordplay that will hopefully give players an even better appreciation for the game once understood.

Store name parodies

As soon as you take control of your character after the opening cinematic, the first thing to likely give you a chuckle are the parodies of store names and billboards found around town. Shibuya is full of chain stores, and depending on the game, companies will sometimes get permission to use stores’ actual names. But in Ghostwire: Tokyo, they’re all parodies. Many of these are well-known stores, so players in Japan that are familiar with them will likely take notice.

“店長の肉” (Tenchou no Niku) is likely a reference to Ore no Yakiniku, a Korean barbeque restaurant that’s part of the “Ore no” chain, including “Ore no Italian” and “Ore no French.” Ore no Yakiniku means “My Yakiniku,” and switching the name to Tenchou no Niku, or something like “Manager’s Meat” in the game gives it kind of a gross nuance. I certainly don’t want to eat manager meat. And when you consider the sign on the front says, “Always hiring managers,” it’s clear that something scary is going on in that kitchen.

Kabazeriya is likely a reference to an Italian fast-food chain in Japan called Saizeriya. Due to their low prices, it’s a popular way for families and students to enjoy Italian food. The name Saizeriya is supposedly derived from Italian, but whether that’s true or not is unknown. However, in Japanese, “sai” is the word for rhino. The in-game name Kabazeriya is taking this “sai” and replacing it with “kaba” which means hippo in Japanese.

“らーめん女郎” (Ramen Joro) looks to be a parody of “らーめん二郎” (Ramen Jiro), a famous ramen shop that uses an especially greasy pork base and one that has inspired numerous other ramen shops. Their ramen is mysteriously addictive, spawning a group of devoted fans referred to as “jirorian.”

Jiro is also a common name for males in Japan, mainly being used for the second son born in a family. On the other hand, “Joro” which is used in the game is an old Japanese word for a prostitute. A clever bit of wordplay. As an aside, it’s also common for brothels in Japan to have names based on indecent parodies of popular stores or movies. If you happen to see a Ramen Joro in real life and step inside, you may not find ramen on the menu.

Incident Homes is a real estate broker within the game. It’s a common sight in Japan to see stores with apartment listings covering the outside windows. But here, the name Incident Homes itself is what stands out. An incident home in Japan is a place where the previous resident either died in the home or had an accident there. Places like that are usually cheaper than usual.

There are also real estate brokers in the real world that specialize in these kinds of properties, like Jobutsu Fudousan. But incidents are generally considered as a negative when apartment hunting, so you don’t see a physical store pushing that aspect quite like Incident Homes.

There’s also Freshmoth Burger, a combination of Japan’s Freshness Burger and Mos Burger chains. “Fresh moth” doesn’t sound enticing like the original stores, though. The game includes many other store names that would never be used in reality. Building names are also rearranged like the Hikarie skyscraper becoming Kagerie skyscraper, switching the Japanese word for light (hikari) with shadow (kage).

With these examples we can see clever uses of wordplay, some of them matching the dark setting of Ghostwire: Tokyo.

Product name parodies

In the game’s convenience stores, players can buy things like healing items and powerful talismans. The convenience store chains that appear as FujiyaMart and Daily Ninja are likely in reference to the actual chains called FamilyMart and Daily Yamazaki. Not only are the store names parodies, but many of the items inside are as well like “和歌コーラ” (Waka Cola), a Coca Cola parody that uses red bean paste as a secret ingredient for a Japanese styled twist. There’s also a magazine on display called “ホッピング” (Hopping), which is likely a Shonen Jump parody with cover art reminiscent of My Hero Academia.

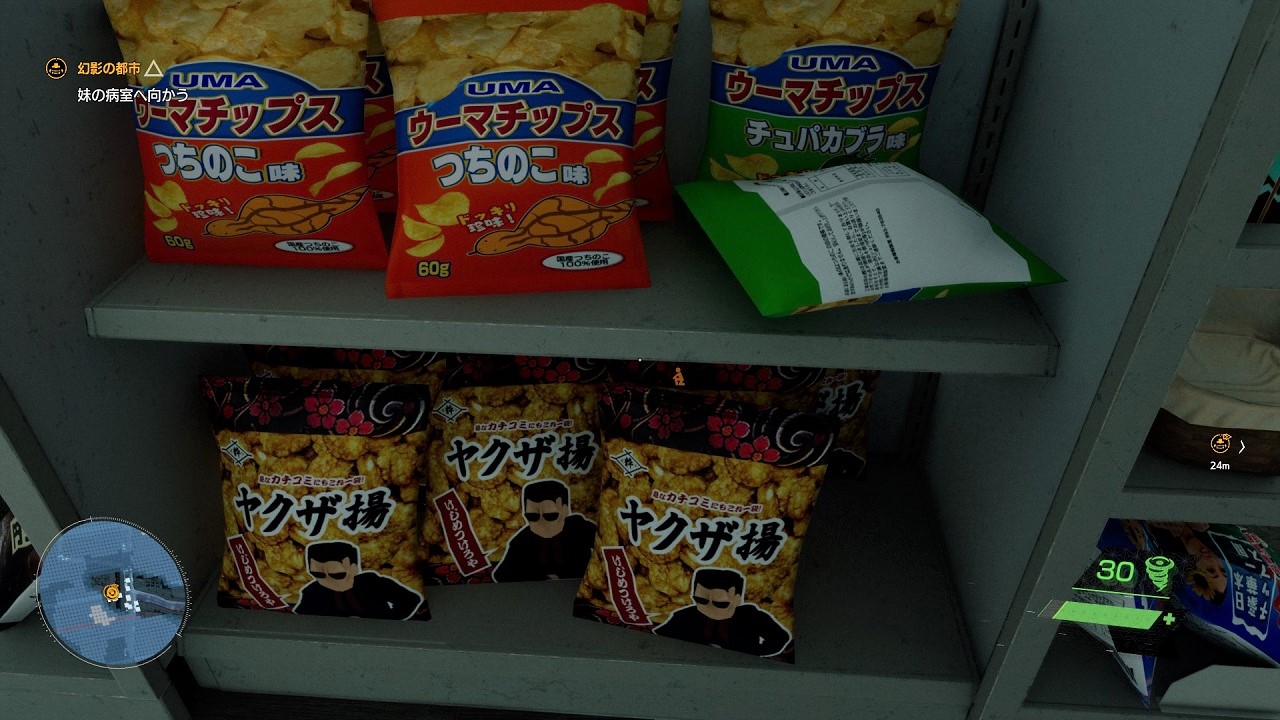

UMA Chips are another little joke mixing UMA (Unidentified Mysterious Animal) and うまい (umai) the Japanese word for delicious. The lineup of flavors is funny too with names like Tsuchinoko and Chupacabra flavor to match the UMA theme. There’s also a fried senbei (a type of Japanese rice cracker) brand that leaves an impression called Yakuza Puffs (likely a parody of a product called Kabukiage). And while their slogan of “Sudden need of a fix in preparation for a Kachikomi (=act of raiding a rival gang)? Have Yakuza Puffs!” is probably a hit with Yakuza members, it’s one others likely won’t forget either.

There are other examples of humorous advertising as well. For example, there is a parody of Cup Noodles called Not Noodles 塩神 (Enjin), with the Japanese characters meaning “salt god.” Not to be confused with Cup Noodles, Not Noodles boasts a “356% increase in salt content” where in reality, noodle brands would advertise a cut in salt content to promote themselves as being healthy. Though it is noble for a junk food brand to make clear how unhealthy it is.

While not a product, the front of one restaurant promotes a “30x the Wasabi Fair” which almost nobody should want to take part in. If you look closely, this kind of amusing text is all over the place.

The food and relic items you can gather in the game have flavor text that do a decent job of explaining the basics about the items (explanations from the menu), but it becomes more humorous for those who are in the know.

Miscellaneous

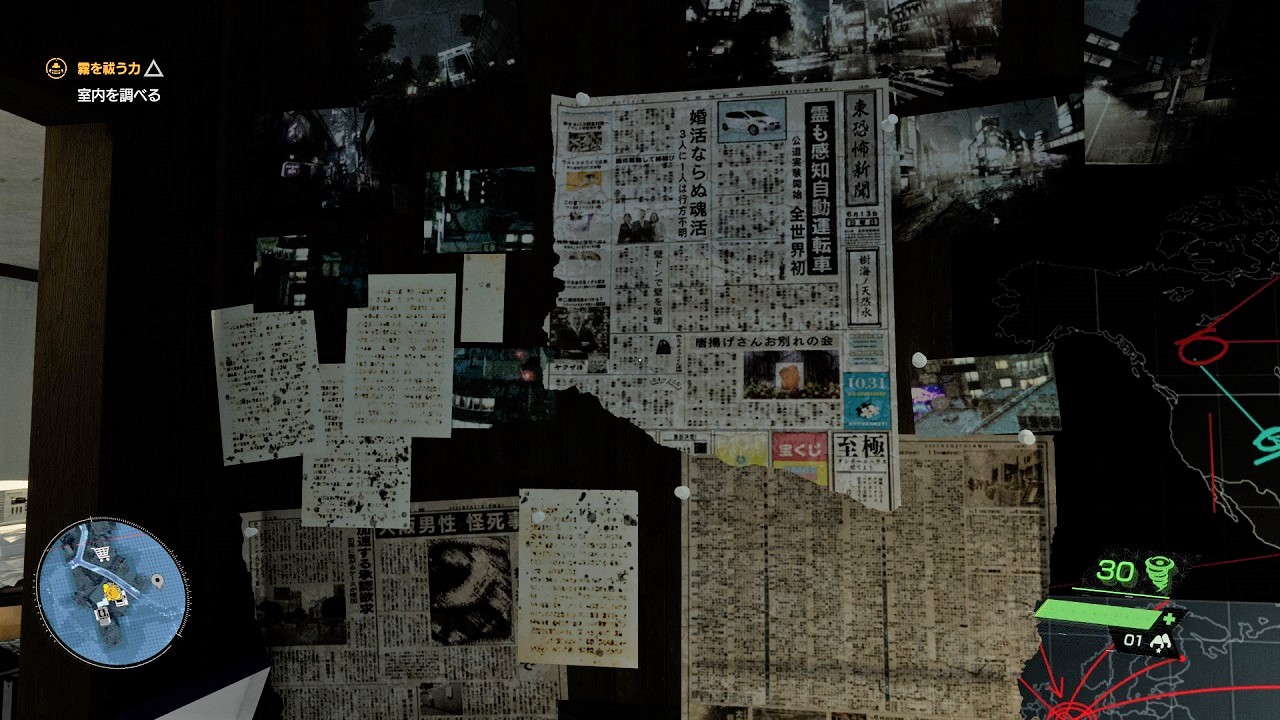

Another thing that won’t easily get across to players that don’t know Japanese is the newspapers in the game. One of them is called Tokyofu Newspaper. In Japanese, “Kyofu” means terror or dread, so mixing that with “Tokyo” is a simple way to give it a spooky feel. And the headlines include things like “Autonomous vehicle that can detect spirits” and “In remembrance of Mr. Karaage ” (karaage = Japanese fried chicken) with each giving off a spiritual vibe. If there was a real newspaper like this, I might have to buy it.

Common sights in Japan’s cities

As stated earlier, Shibuya in Ghostwire: Tokyo is full of humor. But it’s because the game does such a good job of capturing the look of a Japanese city that the wordplay can shine.

Some examples include the recycling bins next to vending machines being clogged with bottles and cans, illegally parked bikes all over the place, and stores near temples keeping their lights less colorful to protect the scenery. It’s a number of small details helping fully realize the world. Convenience stores are sold out of masks and hospitals have notices posted about measures against a new virus, adding environmental storytelling that mirrors the current state of world affairs.

The feel of Shibuya is captured incredibly, but if you look closer, it’s filled with humor and parodies. These two things coming together make Ghostwire: Tokyo’s worldbuilding unique.

Urban legends and Japanese horror movie homages

I also want to touch on the game’s supernatural content. The term supernatural covers a lot of ground though as the game is full of references to urban legends, traditional Japanese yokai, Japanese horror movies, and more.

Let’s start with Kisaragi Station, an urban legend that began its life on the internet. The station name stems from a story posted to the anonymous Japanese message board 2 Chan in 2004 by someone going by the name Hasumi. As Hasumi is on a train posting messages, they eventually arrive at a station that doesn’t actually exist called Kisaragi Station. Hasumi later meets a mysterious person never to follow up with anymore messages.

[Update 2022/03/30 13:14 JST] fixed a typo in the paragraph above.

The collection of detailed posts ended up circulating far and wide, with the story being introduced on Japanese television, being turned into a comic, and being a popular source for content like The Ghost Train from Chilla’s Art, a horror game based around Kisaragi Station. There’s even a movie based on it scheduled to release in Japan this June. And now, even Ghostwire: Tokyo has a side quest based on the urban legend.

The game also features a host of Japanese yokai like the Kappa, Nurikabe, and Ittan-momen. There’s a home similar to the one in The Grudge, a video tape reminiscent of The Ring, and other homages in the game’s side quests and collectible items. While there’s an in-game database that explains more about the yokai, the enjoyment you get from the homages to urban legends and movies will likely depend on your familiarity with the source material.

Wrapping things up

There are lots of games that model their worlds after real cities. Even just ones based on Japan include the Yakuza, Shenmue, and Persona series. But Ghostwire: Tokyo takes it to another level by not only capturing the look, but also the feel through its finer details.

In addition, Ghostwire: Tokyo goes beyond simple virtual tourism by filling the world with humor (+ supernatural entities) and stimulating players’ curiosity. Players can enjoy both looking at a recreation of Shibuya and digging further into the parody of Japan within the game.

For me, it’s a humorous game with bits scattered all around that have made me chuckle. But this might not be the case for players not closely familiar with Japan which is a real shame. But with that said, I understand why they can’t explain every joke in-game. Ghostwire: Tokyo makes it clear just how difficult capturing a local feel and delivering a parody of it to a global audience can be.