Heaven Burns Red officially launched on February 10 in Japan for iOS and Android as a free-to-play RPG, and I wanted to share my first impressions after 25 hours of playtime. What I find most appealing about the game is not the story, the aesthetic, or the battle system, but the back-and-forth comedic banter between the characters. The intentionally cringy Japanese humor is turned up to eleven from the very beginning, and it rarely slows down, at least until midway through chapter 2, which is where I’m at right now.

The text is filled with meta remarks, nonsensical jokes, old Japanese internet slang, wordplay, and references to other works of entertainment. There are some serious and emotional moments later on in the story, but the dialogue is mainly centered around Japanese anime/videogame humor. It’s definitely not for everyone, mind you. I found it captivating, but one of my colleagues said he couldn’t stand how cringe-inducing the text was and gave up playing right after the opening scene.

The latest work from the Clannad scenario writer

The game is being developed and operated by Wright Flyer Studios, a Japanese studio known for mobile titles like Afterlost and Another Eden: The Cat Beyond Time and Space. Key figures include Visual Arts’ Jun Maeda (Moon, Air, and Clannad), who is responsible for the main scenario and music production, and Yūgen (Azur Lane and the Atelier series), who is handling the character design and main visuals.

Story and characters

Humanity is on the verge of extinction due to a series of attacks by mysterious extraterrestrial beings called Cancer. Conventional weapons aren’t effective against them, and the population of Japan has plummeted from 120 million to 8 million. In the midst of this crisis, a new type of weapon called Seraph was invented to counter the threat.

However, not everyone is capable of using the weapon. As humanity’s last hope, girls with the ability to control Seraphs are being gathered at a military base located inside a school campus to train and fight. The story progresses as girls go through training sessions inside the campus and missions outside the campus, while building chemistry between other girls and units. You get to explore each character’s agenda and personal struggles as you progress through the story.

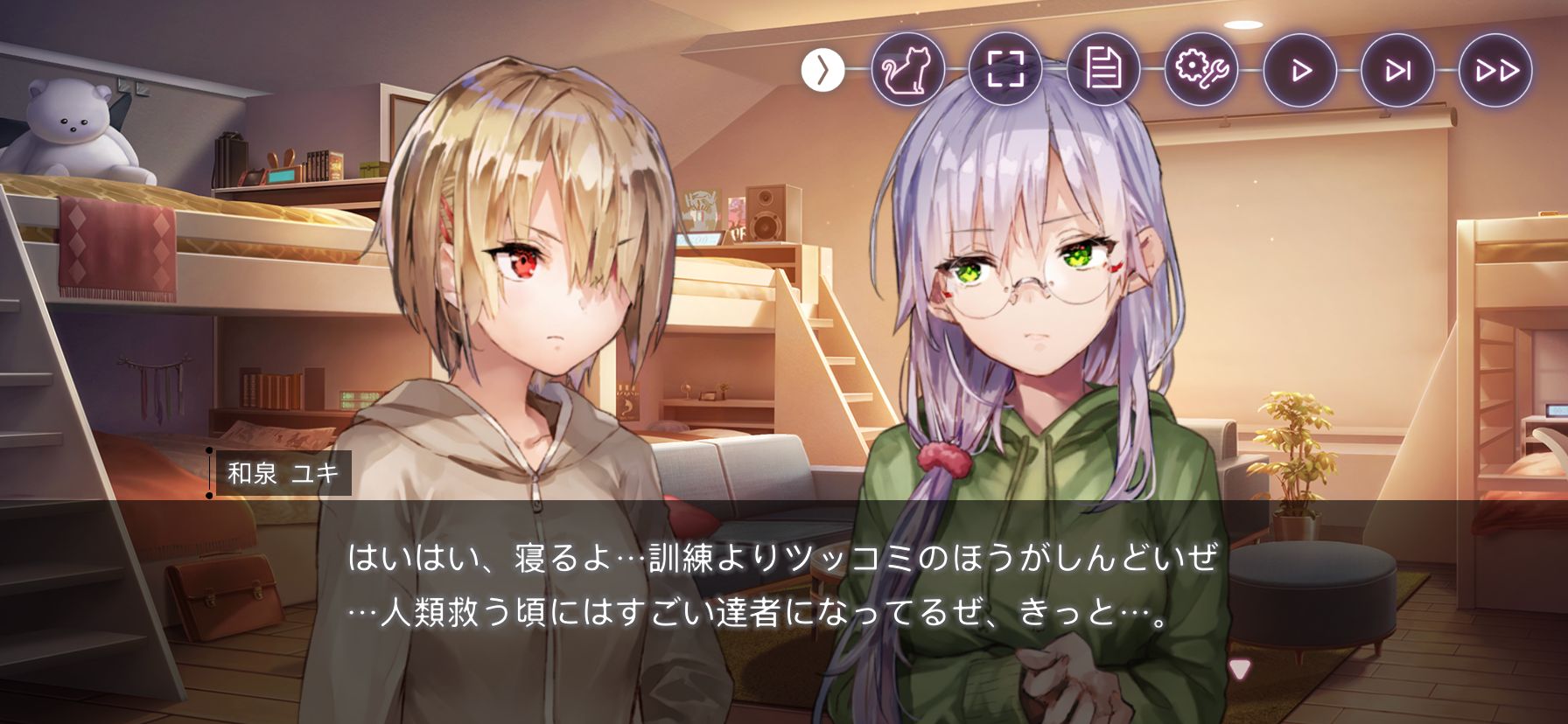

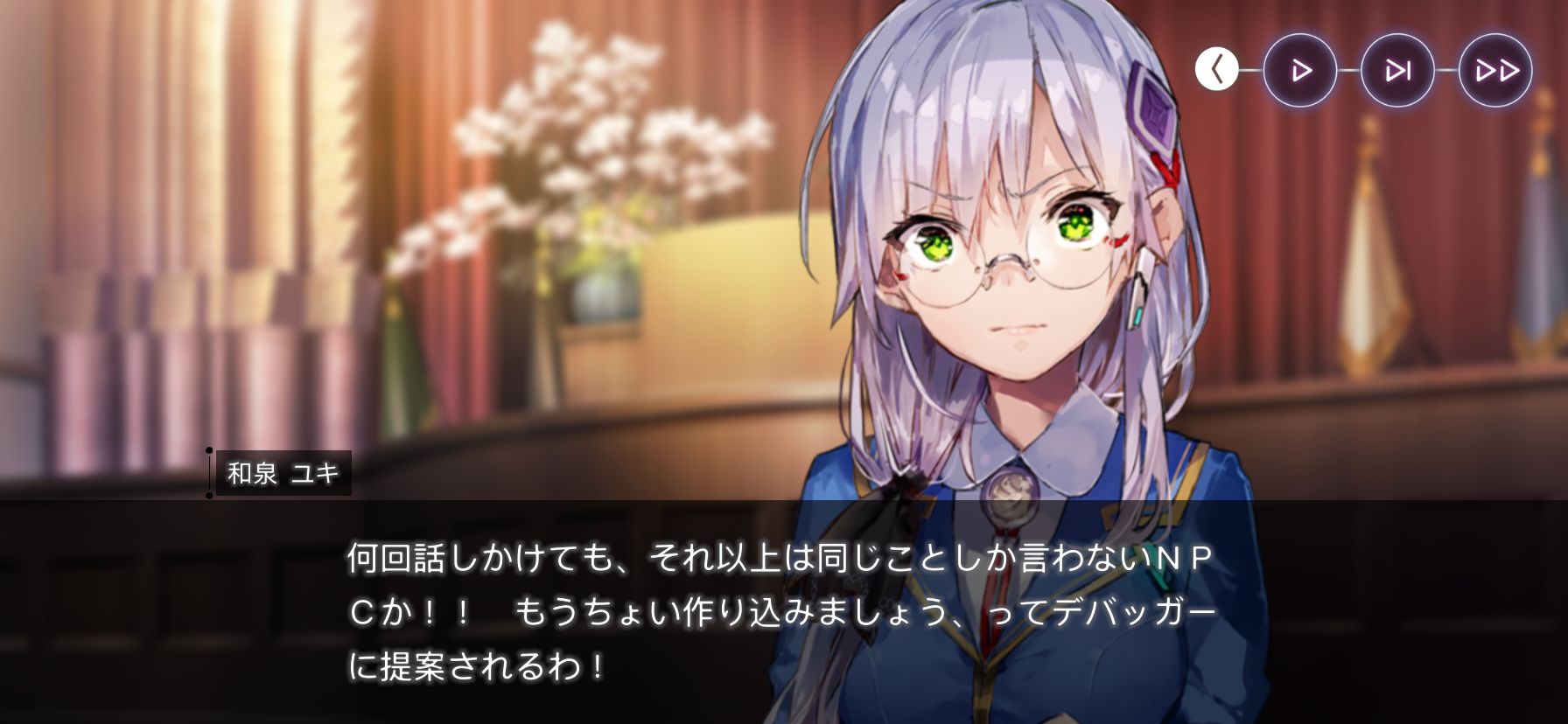

Most of the newly recruited members of the Seraph troop unit 31A, including the protagonist Ruka Kayamori, lack common sense and constantly make offbeat remarks. Each character’s quirks are different, but something is off about each and every one of them, except for Ruka’s sidekick Yuki Izumi. It’s up to Yuki to make this comedy work since most of the dialogue would be just a bunch of gibberish without her intervention.

Yuki’s voice actor Ryoko Maekawa is doing a convincing job so far, expressing Yuki’s caring nature, mild irritation, and exhaustion from being surrounded by oddball characters. I think her character is the most demanding in terms of voice acting, having to show range and nuance to get laughs out of players. Speaking of which, Heaven Burns Red is a fully voiced game, and the absurd exchanges between characters are best experienced with audio on.

Although I’ve been only talking about the comedic side of this game, the scenario writer Jun Maeda is known for making tragic stories with a profound emotional impact on players. In fact, the developers are promoting Heaven Burns Red as a game that would make players cry. This is evident in the commercial footage below, so I’m sure Maeda will eventually lead us to an emotional roller coaster ride full of tears. A glimpse of this happening can already be seen in the game’s first chapter.

Dialogue and translatability

In general, the opening act of a game is usually used to highlight the game’s selling points to attract players’ attention. This applies to the dialogue in Heaven Burns Red’s case since most of the first few hours are spent listening to characters’ nonsensical exchanges with minimal gameplay.

You could say the game is just slow-paced, but I’d say this excessive banter is the main content. Jokes are excessive yet concise. It’s like reading punchline after punchline, and I actually found it easy to digest since each phrase is right to the point without extra fat. That said, whether or not you can tolerate the game’s humor will probably determine your enjoyability.

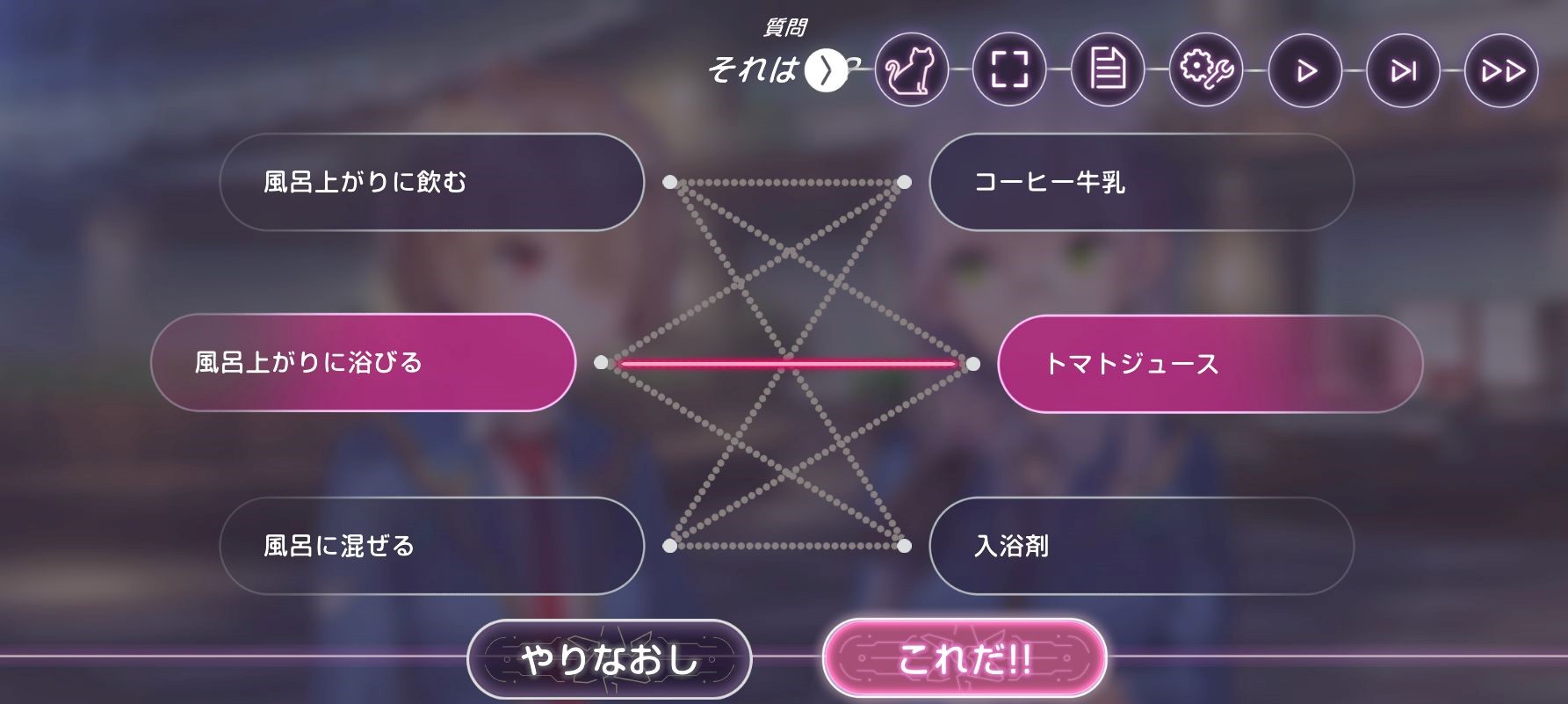

There are dialogue options in the game, and some of them ask you to combine multiple words to come up with your line. You can make some incoherent or absurd lines out of it, and it’s satisfying to hear other characters confusingly responding to your nonsense.

Humor is hard to translate, and I’m really curious to see how this dialogue that relies on Japanese cultural understanding and wordplay will be localized if it ever gets a worldwide release. The same can be said for most narrative-driven games, but the translation would either make or break the experience. Especially with so much humor in it.

Combat system

The game uses a turn-based combat system with an allying party of six characters, three in the front and three in the back. Only the members in the front can attack (and be attacked), and you can freely change the members’ positions during your turn.

The game uses a two-tiered health system in which you first need to take out an enemy’s shield (DP) to deal damage to their HP. To go along with this system, each character is assigned a role. For example, Attackers have abilities that deal massive HP damage, and Breakers have abilities that are effective against DP.

The damage calculation for HP is somewhat unique, with the damage multiplier increasing with each attack. The Blaster role exists to quickly spike the damage multiplier and make the Attackers’ abilities even more effective. Other roles like Healer, Buffer, Debuffer, and Defender (tank), are self-explanatory.

Each character is granted 2 “SP” per turn, which can be used to activate their abilities. Creating synergies between roles by combo-ing abilities and properly managing SP, are the keys to victory.

In addition to the basic weapon attributes of slash, thrust, and strike, there are also elemental attributes such as fire and lightning. It’s preferable to consider type matchups as well when forming your party.

You can toggle on auto-combat while in battles. What’s more, during training battles, which allow you to fight certain enemies consecutively, a power-saving auto-grind mode can be used. When this mode is turned on, the game automatically repeats the same fight for hours, even when the game is running in the background. This feature allows you to collect experience points and upgrade materials when you’re away.

Character progression and gacha system

The character progression system is a familiar one for those who have played other gacha-based Japanese mobile games. There are multiple rarities (styles) for each character, and you can obtain them through gacha pulls. Limit breaks can be done by pulling duplicates.

Characters level up by earning experience points through battles, and you can use upgrade materials to unlock abilities and enhance their stats. There are also items called boosters and accessories that can further enhance the character stats.

I’ve been playing the game for only twenty five hours or so, and I haven’t reached a point where I can answer the critical question of “How far can you go as a non-paying player?” That said, there are some level gating mechanics that require you to grind non-story content or obtain enough characters from the gacha to progress through the story, although nothing too egregious so far. The gacha isn’t particularly generous, though. And in terms of price, a 10-pull gacha costs 3,000 in-game currency (roughly 3,000 yen/$30).

Non-story content

Content outside of the main story includes character events to deepen bonds, hunting quests that offer additional rewards, multi-floor dungeons where you can collect accessories, memory restoration where you can obtain character-specific accessories, and prism battles where you can collect high-tier upgrade materials. The game is structured in a way that asks you to go back and forth between story and non-story content in order to advance.

What bugs me a little is the fact that Ruka’s personality seems to change a bit during side quests (character bonding events), but perhaps that has to do with different writers handling these events. And the dungeons you visit throughout the game are mostly linear and repetitive without giving you a sense of exploration. You just swipe the screen in one direction until you reach the end, with occasional branching paths that lead you to items. At least from what I can tell so far, the level design is a weak point of this game.

Sound and graphics

In terms of sound, the characters are fully voiced, and it adds value to the auditory experience, especially since so much of the dialogue is outlandish. Listening to these lines said out loud is quite a treat. Some of the songs, especially the ones with lyrics, are used effectively during the main story to elevate emotions.

As for the graphics, most event scenes are depicted using visual novel-like 2D graphics, while 3D graphics are used in battles and exploration segments. Conversations during exploration parts are illustrated using 2D character art and 3D backgrounds.

The 2D usage is pretty orthodox, but there are moments where manga-like cut-ins are used to emphasize comedic lines, and some scenes present text in a way that enhance the emotional impact. The 3D graphics and animations are subpar, but the character models are bearable to watch, and combat actions are flashy enough to convey the girls’ powers. I’d say it gets the job done to mesh with the 2D art.

Overall, the best part about the game so far is the comedic interaction between the characters, but that might change depending on how the story unfolds. The combat has some interesting strategic elements but is ultimately mundane, which is especially noticeable when combined with the monotonous dungeon exploration.

With all that being said, I’ll definitely keep playing this game to enjoy the punchline overdose and see how Jun Maeda, a master at making tragedies, will lead the narrative forward.