The official Sega X (formerly Twitter) account shared a PR article by The Japan Times on January 28. The topic of the article – the localization of Japanese games to adhere to Western standards, has since caused mixed reactions in the non-Japanese speaking community, with many gamers expressing disagreement with the idea of Japanese developers culturally revising games for the Western audience. This comes right after Sega’s release of Like a Dragon: Infinite Wealth, the latest addition to a series adored for its unapologetic Japanese-ness.

“Localization VS direct translation” has been a continuously heated topic among fans of Japanese anime and video games, largely fueled by cases of localizations that take too much liberty in adapting or censoring the original script, resulting in altered meanings or “too US-sounding” language. A recent example would be the English localization of Cygames’ “Granblue Fantasy Versus: Rising,” which was criticized for out-of-character dialogue translations and the use of slang such as “simping” and “vitamin D” in unbefitting contexts.

But what is the article that Sega shared about? Essentially, it discusses localization as one of the important factors for successfully launching a game outside of Japan. It describes how localization has, over the years, improved in quality and become properly standardized.

The SEGA of America localization team comments that localization has changed in favor of being “more faithful to the cultural and emotional content of Japanese games than ever.” While this is an ideal all gamers will likely agree on, the problem probably lies in the next idea presented: “The player, whichever country they’re from, should understand and feel the same thing as someone playing in the original language.” Judging by what users have been saying in response to Sega’s post, players (especially the kind that enjoys the Like a Dragon series) want to experience Japanese games as “Japanese games,” i.e., they want the feeling of the game being “culturally foreign” to be preserved, rather than having things adapted and estimated to (often not close enough) western equivalents.

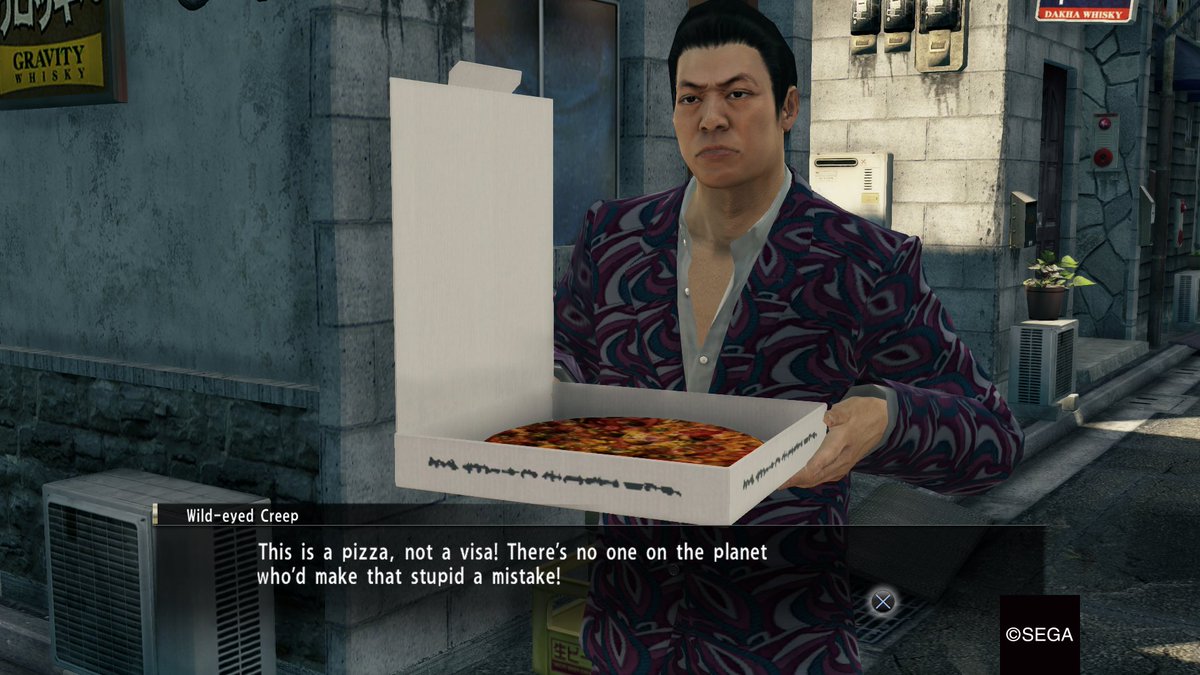

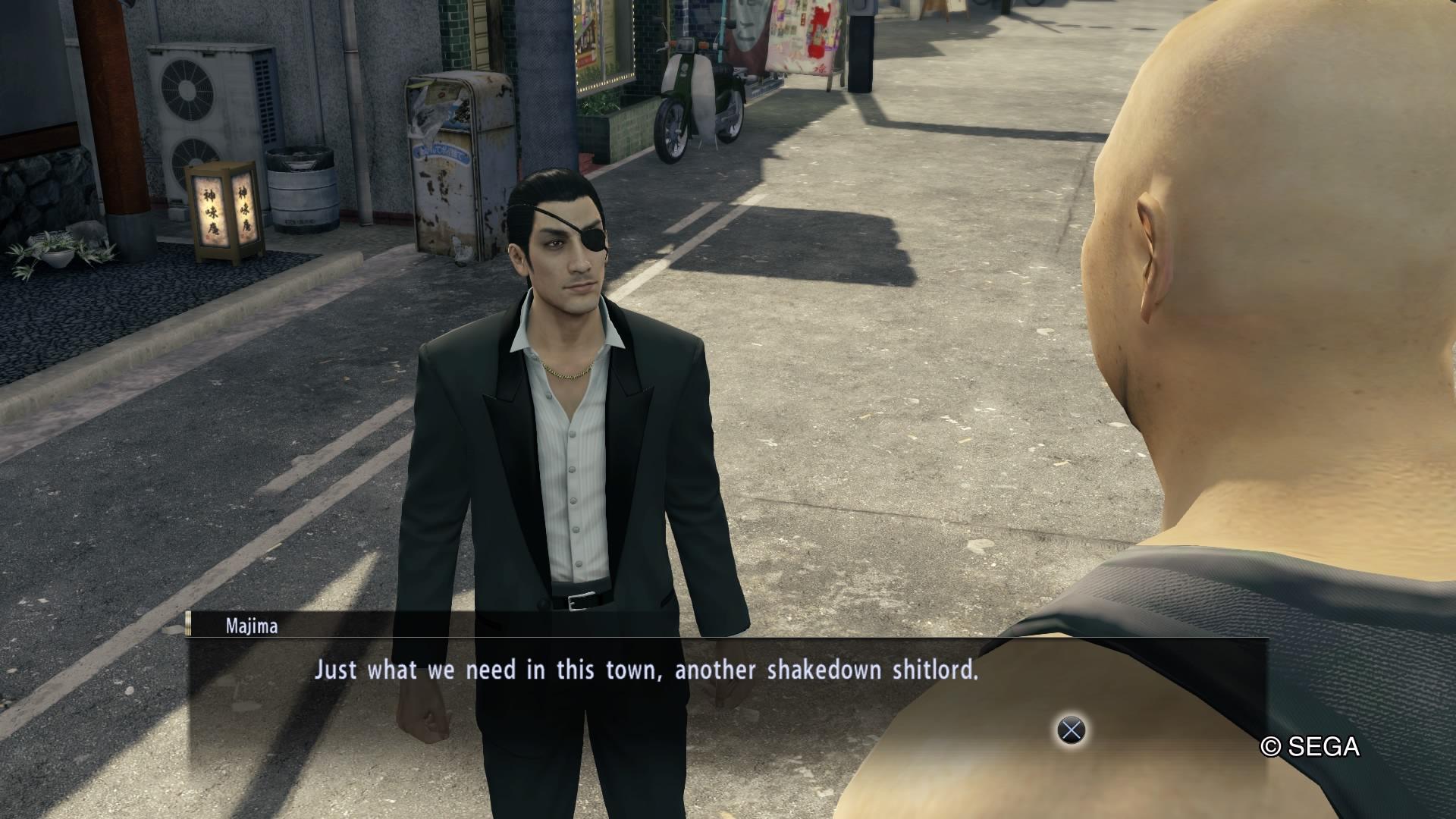

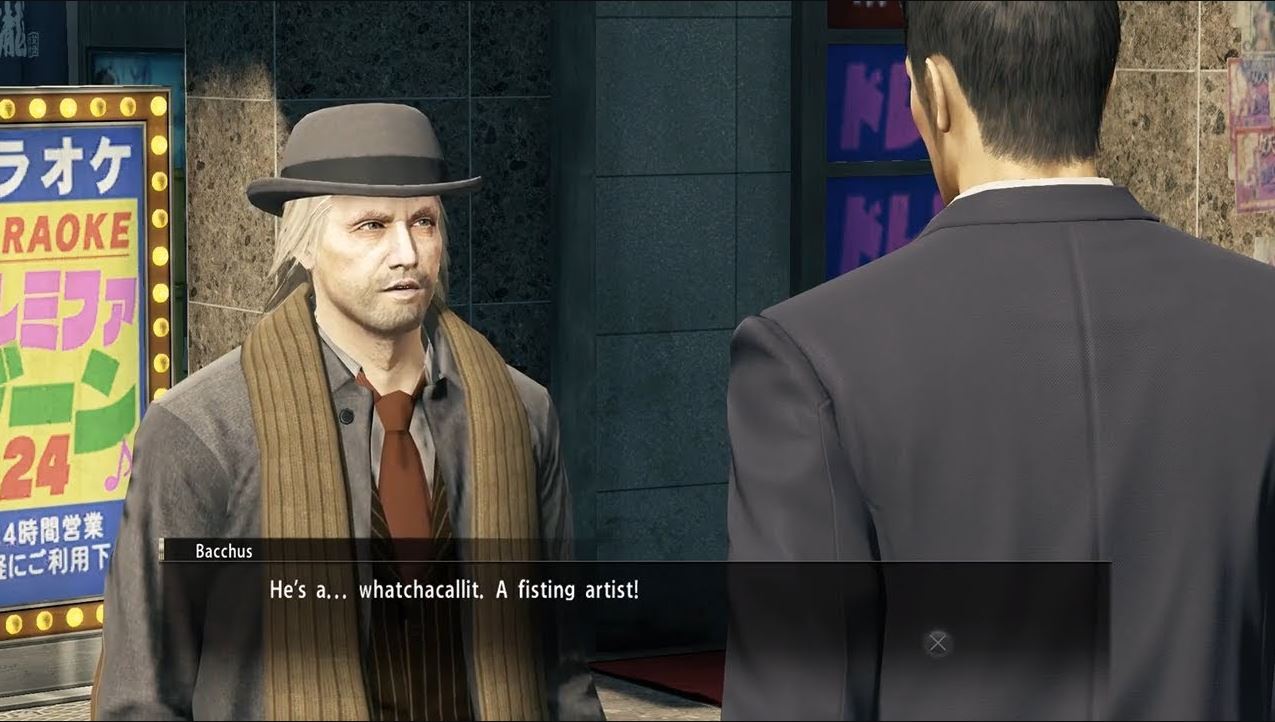

It would appear that, for non-Japanese speaking players, a big part of the fun in Japanese games comes from encountering concepts and phrases that can only be found in a Japanese game, as well as getting an unfiltered insight into social climates in Japan and the minds of Japanese creators. This is also related to another point video game localization is criticized for – alterations that make the game’s content more acceptable in relation to western societal standards. Many users believe localizers make (or are instructed to make) too many changes that interfere with a work’s original creative expression, putting them into a position closer to co-authors than localizers.

Obviously, “no more localizing anything” is not a solution, as video games, much like literature, cannot function by literal translation alone (particularly with a language pair as drastically different as English and Japanese), but it is important to recognize that localization can be done in varying degrees – some of them just right, some of them excessive. Coincidentally, the Like a Dragon series is known for a lot of good-quality, memorable localization, and Sega made a good example of “delocalizing” to just the right amount by renaming their signature IP.

Sega made the decision to rename the “Yakuza” series the “Like a Dragon” series as the word “yakuza” is nowhere to be found in the original Japanese titles, and more importantly, has a negative ring to it to the Japanese ear. Speaking for The Japan Times, the director of Ryu Ga Gotoku Studio Yokoyama Masayoshi commented, “Having the word ‘yakuza’ in the (English) title harms sales in Japan,” (…) “Japanese society is getting tougher and tougher toward yakuza. In the past, we could talk about it on television, but it has become a taboo word.” While the word “yakuza” may sound cooler and “more Japanese” to non-Japanese players, doing away with it actually did a better job of conveying the modern Japanese mindset.

On the other hand, the Sega localization team makes the remark that, thanks to Japanese culture becoming more popular, localization has become easier, commenting: “People know what ramen is now … we don’t need to say ‘noodles’ any more.” But ironically, if all localizations of Japanese media had been sticking to “noodles” to refer to ramen throughout the years, it’s questionable how many people would get to know the dish’s real name.

This exemplifies how important it is to strike the right balance in localizing – if every second term is obscure and followed by long footnotes explaining them, no modern player will have the patience to play. On the other hand, if everything that makes a game Japanese is replaced by vague western equivalents, this can spoil immersion just as much. Going forward, developers may be held to increasingly high standards in terms of making sure this balance is achieved.

Respectfully, I don’t think dogpiling by a small portion of trolls who misunderstand Sega’s stance on localization constitutes as controversy, and unfortunately this article lacks director Masayoshi Yokoyama’s follow-up to the Japan Times article:

https://x.com/yokoyama_masa/status/1752682081531085216?s=20

To sum it up, he states that localization can never change the actual content of a game, localization’s goal is to take ideas, that when translated literally don’t come across so well, and make them palatable to players in other markets without changing fundamental meaning, etc. Ultimately, I think the content of this article is informative, but the headline and opening statements are needlessly inflammatory — the trolls on the wrong side of this culture war are louder than they are significant.